Ease and Ethics of User Profiling in Black Mirror

Workshop on Re-coding Black Mirror - co-located with The Web Conference (TheWebConf)

✍ Harshvardhan J. Pandit* , Dave Lewis

Description: Discussing how the real-world is already a reflection of the Black Mirror episode 'Nosedive'

published version 🔓open-access archives: harshp.com , TARA , zenodo

📦resources: Ease and Ethics of User Profiling in Black Mirror

Abstract The use of personal data is a double-edged sword that on one side provides benefits through personalisation and user profiling, while the other raises several ethical and moral implications that impede technological progress. Laws often try to reflect the shifting values of social perception, such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) catering to explicit consent over use of personal data, though actions may still be legal without being perceived as acceptable. Black Mirror is a TV series that serves to imagine scenarios that test the boundary of such perceptions, and is often described as being futuristic. In this paper, we discuss how existing technologies have already coalesced towards calculating a probability metric or rating as presented by the episode `Nosedive'. We present real-world instances of such technologies and their applications, and how they can be easily expanded using the interminable web. The dilemma posed by the ethics of such technological applications is discussed using the `Ethics Canvas', our methodology and tool for encouraging discussions on ethical implications in responsible innovation.

Introduction

Personalisation of services is the mantra of today’s applications and services. In the pursuit of better features and more accurate results, the garb of progress is often drawn over any ethical or moral implications that might arise from misuse of technology. Such actions are often defended as being legal, but are not necessarily in line with the society’s or an individual’s moral and ethical standings, which change over time. The law in itself is slow to catch up to such changes, with one example being the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) [1] that aims to enforce the use of personal data as an explicitly consented transaction. Such laws are often bound in rigid frameworks and require the decision of courts to resolve ambiguities and provide decisive directions for its application. The long duration between the discussion, creation, and application of such laws provides a certain leeway for organisations to use resources in ways that are controversial if not outright unacceptable to sections of the society.

User profiling is one of the more controversial technologies that has become the focal point of discussions regarding personal data and privacy. Its applications provide a greater measure of personalisation and convenience to the users. At the same time any misuse, intentional or otherwise, has consequences that polarises social debates against the technology itself. In such cases, it is difficult to establish a balance of narrative between the two sides. As we move ahead in shifting paradigms towards using artificial intelligence and machine learning, the dependence on actionable data about an individual will also increase. Issues related to ethics and acceptable uses of technology will become increasingly critical to their creation and usage. It is therefore not difficult to envision the argument towards making ethics policy a legal requirement and necessity in the distant future.

Fiction, particularly those like the novel 1984 by George Orwell and the TV series Black Mirror by Charlie Brooker, serve as a focal point of discussion due to their perceived similarity to the world of today taken to an undesirable future. The blame in such cases is often put on the technology being applied, a point emphasised constantly by the various discussions surrounding episodes of Black Mirror. The assumption of such discussions and perceptions is that the technological advancements are far off in the future, and therefore, there is a sufficient amount of time where interventions can take place to prevent them. The reality, as we discuss in this paper, is that we are already at a stage where the technologies exist, though in a comparatively crude form, and it is the application of these that provide causes of concern. We particularly take the example of ‘Nosedive’ (Black Mirror S03E01) to present user profiling using current technologies. The focus of our discussion is on presenting the ease with which such technologies can be combined and deployed using the medium of the web, which has permeated into becoming a basic requirement for most people across the globe.

A ‘solution’ to the conflicts presented by such technology can be practising reflective research and innovation where the creation and application of technology obligates an discussion on its ethics as part of its development. Currently, we lack the necessary mediums and frameworks to provide a sustainable alternative to existing business practices that do not encourage the required discussions. There are ongoing efforts that aim to change the status-quo of this situation, and like all good things, need to be pushed and disseminated across the spectrum. We present one such methodology - the ‘Ethics Canvas,’ based on the ‘Business Canvas’ [2], to discuss the ethical aspects of the aforementioned Black Mirror episodes to advance the discussion of ethics related to technology.

The rest of this paper is structured as follows - Section 2 describes the current state of user profiling practised by commercial organisations and governmental institutions across the globe. Section 3 describes how these can be used to formulate a Nosedive-like rating system. Section 4 discusses how the rating system affects the users and the need for practising responsible innovation. Section 5 presents the Ethics Canvas methodology and tool with a use-case. Section 6 concludes the paper with a call for collaborative discussion towards adopting responsible innovation practices.

Real World User Profiling

The web is an important medium of communication and of information dissipation. It has permeated social constructs to the point where it is often considered as simply being interminable and omniscient. The adoption of this medium for communication has turned it into a social requirement - a behaviour seen increasingly in younger sections of the populace. The means through which the web, or the internet, is accessed is using the browser, or some variant of it which forms an interconnect between a local service and the internet. Devices used vary from smartphones which are extremely personal devices to community computers which may be shared between a large number of people. These distinctions, which earlier presented a challenge for user tracking, are now considered to be an opportunity due to technologies like supercookie and browser fingerprinting [3]. These trackers feed information into information silos, where each profile is processed to generate some form of likely metric reflecting the probability of an action.

Organisations such as Google and Facebook build up such profiles [4] to identify the probability of an ad having the maximum intended effect - that of buying the product. Current approximations put the information usage at ads being targeted towards users (and not the other way around), but this does not deviate from the possibility of using this information to identify certain inherently personal characteristics about the user. The most popular example of this is the use of social information in targeted electoral campaigns where personal information is used to identify and influence electoral demographics. In its simplest form, this information can be used to ‘rate’ a user to how pro- or against they are for a certain election or party. Even the availability of this information to third parties could be a cause of concern and result in severe conflicts of interest.1

User profiling is prominent and widespread in financial sectors, where it runs rampant with legal blessing.2 Financial institutions such as banks, insurance providers, and credit rating providers collect a large trough of personal information to profile users and generate some financial metric represents the individual’s monetary status. How this information is collected, or used, or shared is transparent to the individuals. Even with new laws being created and enforced, the credit industry shows no plans of stopping.

The collection, usage, and sharing of such information is inherently possible because of the permeability of the web, which provides a robust framework for services to operate at a global level. Each information holder has vested interests to hold on to their data and share it only for significant gains such as monetising. As the availability of this data becomes common or easy to collect, the organisations monetising this resource must evolve to generate new types of data which are not readily accessible. One example is the aforementioned likelihood of targeting electoral support such as in the case of Facebook ads.

With the growth in the availability of information on the web via channels such as social media and user tracking, it becomes possible for multiple organisations to have collected the same types of data. In such cases, the defensive strategy of holding on to data would no longer apply. Instead, additional value would be pursued by combining data across information silos to create a more comprehensive user profile. Governmental agencies associated with information collection and defence are already implementing such strategies to combine their data troughs across different agencies into one location. In the future, commercial entities are likely to do the same.

Building up a user profile is entirely dependant on the amount and categorisation of personal information available for profiling. Currently, each organisation, whether commercial or governmental, depend on collecting the data and processing it themselves. Service providers have sprung up to provide information analysis as services.3 However, such approaches still lack a uniform mechanism for combining all available information under a single identity to generate models that extract richer metrics for individuals. The inherent unwillingness of information holders to share or collaborate on creating such a mechanism has worked in the favour of the user as it prevents combining the different information graphs.

However, with government mandated identifiers such as Aadhar (Govt. of India) [5], it is not only possible to identify an individual across any service they use, but also to prove their identity biometrically. With various sectors aggressively making the linking of an Aadhar mandatory4, it is only time until information can be reliably linked across organisations. In such cases, analysis and provision of metrics are likely to rise as specialised service providers.

Implementing Nosedive ratings

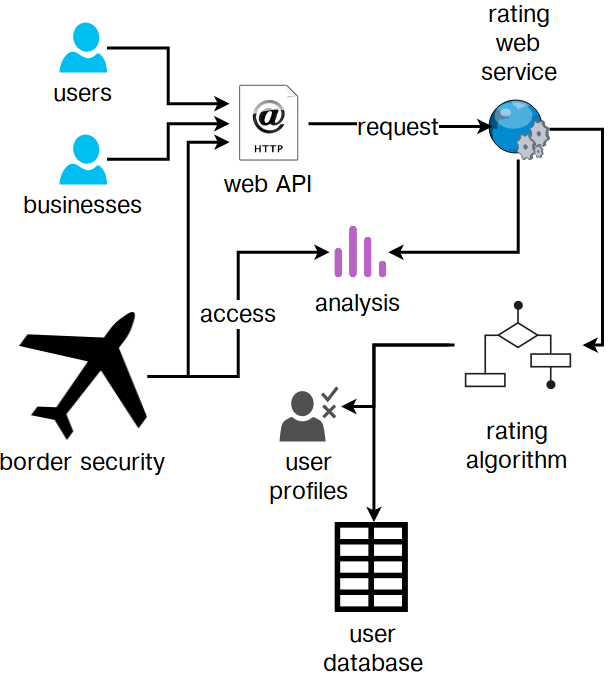

In the Black Mirror episode Nosedive, each individual has an inherent rating5 that everyone else can see. Users can rate each other, which changes the rating. The key question (unanswered in the episode) is who maintains the rating - is it a government undertaking, or is it a commercial provider. We can find a clue in the use of such ratings by governmental security agencies such as at the airport where flying requires a 4.2 minimum rating. This implies either that the ratings are maintained by the government directly or outsourced, or some organisation, likely commercial, maintains these ratings that the government uses to restrict flying at airports. In both cases, the user’s rating can be considered to be personal information, and yet it is considered public. The user has no right or control over how this information is used or accessed, making comparisons to the use of social media by border security inevitable. An overview of the user profiling workflow is depicted in [fig:nosedive].

In reality, such a rating system is much less likely to be purely regulated by users, and instead would be maintained by some organisation with governmental overseeing [China rating system]. The required information would be accessed by collecting data from existing parties instead of setting up a information system from scratch. This can result in a collaboration between various organisations, both governmental and commercial, to create a system where individuals are rated or scored. The complex task of establishing identity can be overcome through identification schemes such as Aadhar, which provides a web-based API for verifying authentication of individuals via thumbprint, or alternatively, can be used to retrieve identification of individuals. With technology such as facial and iris scanning becoming available,6 these can be added to further extend the database and its identification mechanisms. Such a system would naturally contain legal provisions to prohibit its use for commercial purposes.

However, as has been demonstrated repeatedly, organisations manage to find loopholes or ways to subvert the law. In this case, an organisation can use the identification mechanism to identity the individual, after which it can match the identity with a virtual one in its database and claim legal compliance as it can use the virtual identity for providing its services and user profiling.

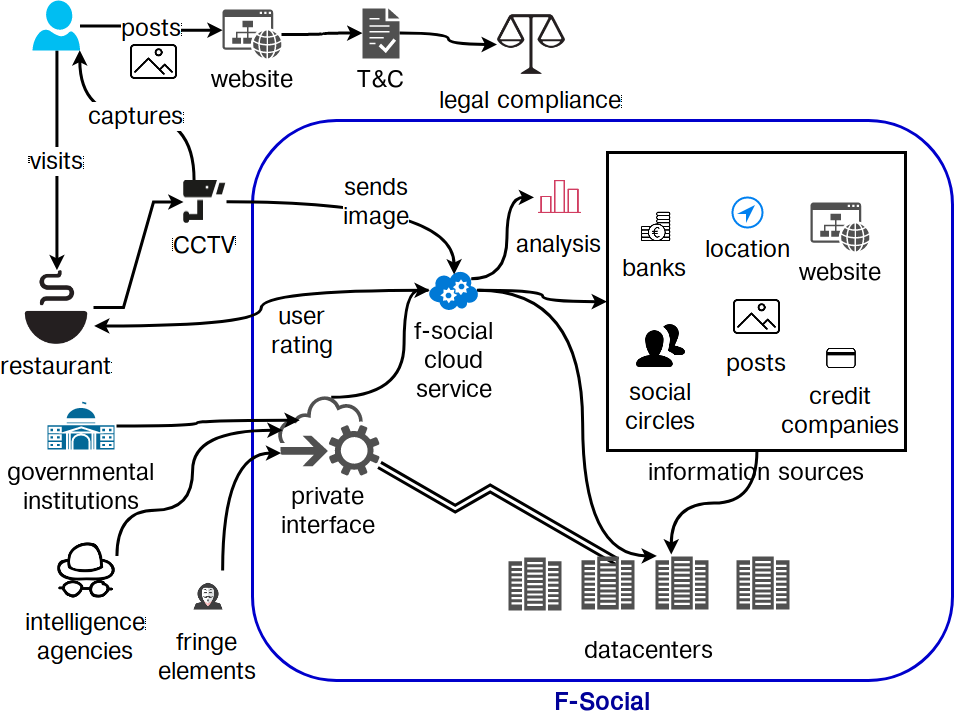

Let such a fictitious organisation be called F-social that provides some services to the users (free or paid) and manages to rack up a lot of personal information which they ‘promise’ not to share with third parties. Their legal documentation, however, says that users provide this information for any use by F-social, which means that they can use this however they please. While this may not be acceptable under GDPR, most users are likely to be ignorant of legal implications and would continue to use the service even if all uses were outlined in the terms and conditions. Under GDPR the intended processing activities need to be mentioned while obtaining consent from the user, which means that if F-social finds some way to obfuscate the activities behind legal-speak, users would be accepting the terms anyway. It remains to be seen how the law will be enacted as it comes into effect from 25 May 2018. [fig:fsocial] presents an overview of the scenario described in this section.

F-social uses all the information it has gathered to provide a metric or a score for an individual that reflects the likelihood that the individual fits a certain profile or pattern. No personal information is leaked or shared apart from the requested metric, which is not deemed personal information as is generated by F-social. [footnote: it would take a large and time-consuming court case to try to establish that this metric is indeed personal information, and the proceedings may be delayed for years. In addition, the courts would only decide over a region, which means some regions might allow F-social to continue running.].

A restaurant sends in facial pictures of its customers to F-social to get a metric of the amount of purchasing power they possess and how likely they are to splurge. They are able to do this via a seemingly innocuous notice at their doors that says “by entering the premises you consent to be identified.” F-social identifies the individuals by associating their unique facial profiles across its database of users. If that individual is not on F-social, it is able to identify the facial fingerprint from the photos uploaded by their friends. If there is absolutely no information, F-social returns the “no match” result, which is interpreted by the restaurant as being ambiguous and suspicious.

To calculate a score of the individual’s purchasing power and probability of splurging, F-social looks to its graph of information. It considers the past purchases posted to its site, or obtained via financial data trading with banks and insurance agencies. It checks for what kind of dishes were ordered, whether these were expensive or cheaper. This provides it with an estimate of the individual’s purchase capacity and history. F-social then looks to the user’s personal information to see if any special occasion is within a certain timeframe. This could be a birthday, an anniversary, a promotion, or a paper acceptance if they are an academic. F-social also tries to gauge how far along they are from their monthly salary. Its assumption is that individuals splurge when they have an occasion or when they have an temporal excess of money. Based on this complex and complicated calculation, F-social sends a metric of the individual’s purchasing power and splurging capacity. In no way is personal information directly being transferred between F-social and the restaurant, and yet, one can intrinsically see the violation of some ethical construct of information being traded this way. The individual in question has neither the awareness nor the control over this information exchange. Additionally, the information being stored and accessed is completely abstracted from the outside world. If it was obtained by some third parties without a legal route, it is impossible for the individuals to have ever known about this. Another quandary is posed by governmental supervision and access to personal information. This is not far-fetched from the way the user rating is used in Nosedive to prevent the character from flying as she is deemed to have a ‘low rating,’ that is interpreted as being not safe or cannot be sufficiently vetted to be allowed to fly.

This second-hand effect of limiting access or discriminating based on some metric results in a pressure to conform to accepted behaviours. If patrons knew that posting on F-social would increase their chances of getting into the restaurant, chances are, most would try to post things. F-social can also influence this behaviour by controlling the way things are viewed on its site. If more posts about the restaurant start appearing on the feed, it creates a psychological want to be included in the group by going to the restaurant yourself. Influencing an user’s feed with posts from people who have a larger metric can create an artificial want to increase one’s metrics as well. This is amply seen in Nosedive where the character tries to attend a wedding with the intention of increasing their own rating. In such situations, the parties involved in the rating process are the ones that control the narrative with the users being under the illusion of having control.

Legally, F-social and affiliated parties may be in the clear data protection laws not being strong enough to counteract against it, or by acquiring the user’s consent in a manner that does not portray the complete extent of its ethical implications. In such cases, the only choices left to the user are to petition for a change in law (e.g. through elected representatives) or to leave the service. This status-quo thus puts the users at a disadvantage.

Responsible Innovation

The world wide web, also known commonly as the web or the internet, provides a foundation for large-scale sharing of information across the globe and is the basis of a vast number of commercial entities that depend on it for their business. The basis of the web is protocols or standards that are used as a mutually understandable form of interoperability for exchanging information. This can be done via websites or abstract interfaces (also known as APIs) that let people interact with data in a semantically richer way. While advances in technology increasingly depend on this connected nature of the web, we see cases where the very foundations of the web are used to subvert privacy considerations in various ways. One way this is done is by controlling and modifying packets in the connection by the service provider7 that allows injecting ads as well as selectively throttling traffic. While such practices may or may not have legal repercussions, they are certainly a cause of alarm regarding privacy. The control over internet packets effectively allows an identification tracker to be inserted in to the web-packet itself, which may allow any website or service to identify the user (at some abstract level) thereby further advancing the use of non-explicit information in user profiling as outlined in the previous section. While such activities can be subverted using laws and public pressures, both of these can be very difficult or time consuming to take effect. Meanwhile, this cannot be used as a means to establish control over the web or to ban it or to restrict its usage in the sense of usage.

A practically viable solution is to increase the level of awareness of the general user to better prepare them for the choice they make when handing over consent or agreeing to use a service. Terms and conditions are a legally mandated way of doing this, but they have been proven to not be effective at all due to the density of the text. GDPR mandates explicit consent that must be obtained by making the user aware of all the ways their data will be used. This approach is certainly progressive, but it is not going to stop user-profiling across the web. Trying to paint the entirety of activities related to user-profiling in a negative light would be to restrict progress in technological advancements. Therefore, we must try and come to a middle ground where progress can take place alongside addressing any practical issues the society may have at large regarding the use of such technologies. This is where the field of responsible innovation can be adopted as a good practice alongside existing approaches such as secure websites and privacy policies.

The basis of responsible innovation is that of building conceptions of responsibility on the understanding that science and technology are not only technically but also socially and politically constituted [6]. In commercial interests, the considerations of privacy and ethics have begun to take shape but are still in their nascent stages and have no effective methodology that can be integrated with business practices. The current norm seems to be to consider the practical implications of an technology after its widespread usage and in most cases only when someone else raises objections based on their perceived risks. There also exist challenges in addressing the uncertainty of technology being used and its rapid change and proliferation.

Instead of looking for a paradigm change in the way privacy and ethics are handled on the web and by organisations, we look towards the core issue underlying the lack of discussions on these topics by technologists - which is that no method for practising ethics integrates into the methodology for work readily enough to adopt it. Another challenge is the perceived authoritarian requirements for discussing ethics, which are not only not true, but also hinder discussions about these topics in open spaces such as those on the web. While privacy policies aim to discern concerns related to privacy, no such tools or practices are in usage for ethics which remains a topic of discussions that are either closed-door or absent from public view.

One way to address this to is to better enable users to tackle the responsibility of understanding technology and its effects on privacy and ethics. While it may not be practical to engage all users in an discussion either one-on-one or as a community, it is certainly practical and possible to present a discussion to the users about the ethics of technology. This will empower the users to ask questions such as “what am I providing and what am I getting in return?” and more importantly - “what are the risks? are they worth it?” These are inherently personal questions whose answers change from person to person. This is analogous to privacy policies that aim to describe the considerations about privacy but without a proper structure and a methodology, lack the necessary depth as well as guidance on how to approach the issue.

Ethics Canvas

We developed Ethics Canvas as a novel method to address these challenges using a tool that encourages discussions pertaining to practising ethics in research and innovation. We evaluated existing approaches of responsible innovation [7] which are focused on the design of business but not on technologies involved in the innovation process. To integrate a discussion of ethics into existing methods of discussions, we used the Business Model Canvas (BMC) [2] which allows collaborative discussions about the business and encourages a common understanding of how the business can create, deliver, and capture value.

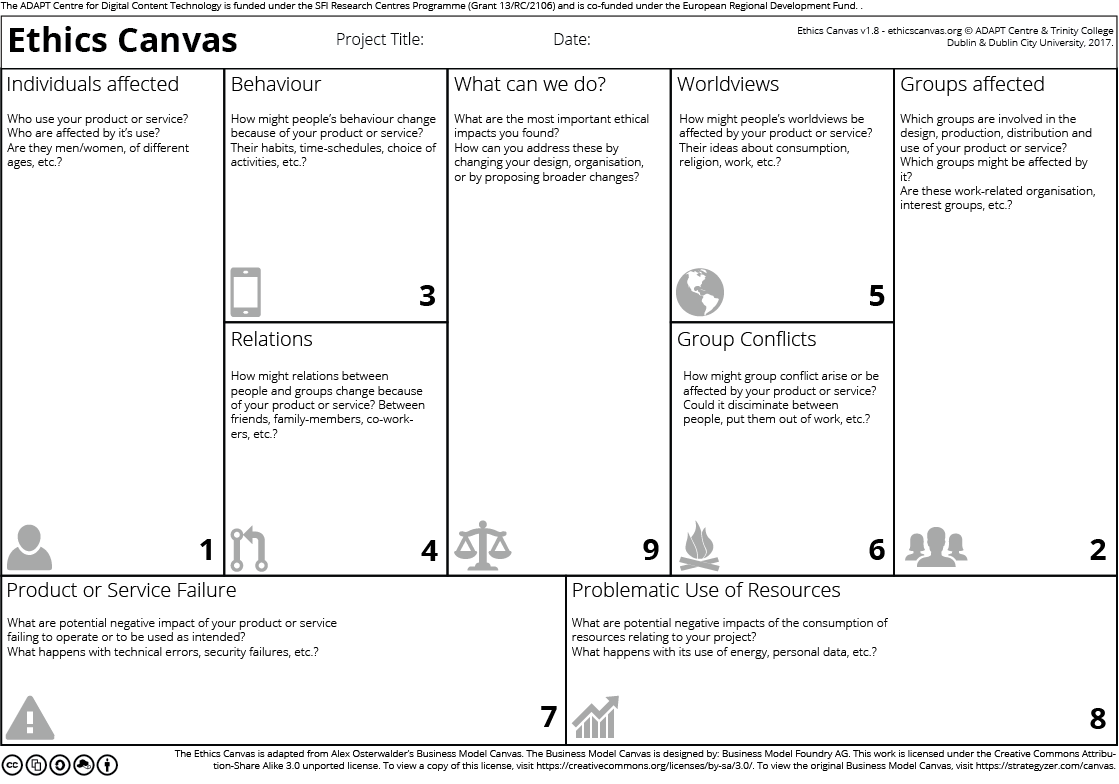

The Ethics Canvas helps structure discussions on how technology affects stakeholders and the potential it has for ethical considerations. Currently at version 1.9, the Ethics Canvas has evolved over time to better capture and reflect discussions. It consists of nine thematic blocks (see [fig:ethicscanvas]) that are grouped together in four stages of completion. The first stage (blocks 1, 2) requires identifying the stakeholders involved based on the technology under consideration. These are then used to identify potential ethical impacts for the identified stakeholders in stage two (blocks 3-6) and non-stakeholder specific ethical impacts in stage three (blocks 7, 8). Stage four (block 9) consists of discussions structured around overcoming the ethical impacts identified in the previous stages. The ethics canvas can be printed or used as an web application that can be used without an account and can be downloaded. Certain features such as collaborative editing, comments, tagging, and persistence are made available through an account. The source of the application is hosted online and is available under the CC-by-SA 3.0 license. We are working on the next iteration of the canvas and intend to exploit web technologies to provide a cohesive experience around discussing ethics. We welcome ideas, suggestions, and collaboration regarding the same.

We take the example of Nosedive, and the scenario presented in this paper of achieving such a situation through aggressive user-profiling, and use the Ethics Canvas to discuss its ethical implications. The canvas itself used for this example is available online and is provided hereby under the CC-by-SA 4.0 license.

The first stage involves identifying the types or categories of individuals affected by F-social and its services for providing metrics or ratings. Alongside users of F-social, this also includes any user (or individual affected by) of the organisations using the service for obtaining ratings. In the hypothetical scenario, this would include customers of the restaurant. This would also include any individual that is not on F-social but who is present in a picture or mentioned in a post. Extending this to all information sources used by F-social, if it uses any dataset of individuals such as from credit companies, then any individual in that dataset should also be included in this stage. For groups affected, these would be people averse to being tracked such as journalists who might wish for ‘safe’ places for meetings. This would also include people in positions of power such as politicians or bureaucrats where information about who may inadvertently be present at the restaurant could lead to misuse. Any category of minorities who might inadvertently be aggressively profiled are also at risk.

In the second stage, we explore how these stakeholders might be affected by discussing the potential ethical impacts of the technology. With respect to behaviour, users might find more incentive to post things that positively affect their ratings and refrain from posting negatively affecting things. They are also more likely to provide information if it helps them achieve monetary or other forms of benefits from services that use the ratings to vet customers. This behaviour might encourage an acceptance of invasion of privacy as the legally the users would be willing to provide the information for intended use by F-social. In terms of relations, if ratings take into account the social circle, then users are more likely to want to have their social circle made up of people who would have an positive effect on their rating. This is seen in Nosedive as well where people try to be nicer to others who have a higher rating than them in the hopes of increasing their rating whereas the inverse of this invites people who have higher ratings to treat those with lower ratings with contempt. This will lead to a change in the general perception of individuals and places based on the ratings and metrics they cater or reflect. For example, places that only cater to people with higher ratings automatically are seen as ‘exclusive’ whereas places that readily accept people with lower ratings might be seen as not being ‘classy.’ To a certain extent, this phenomenon is observable today with regards to monetary spending capacity. This leads to a natural resentment of each group towards the other which might be open for exploitation by fringe elements of the society for their benefit. A layer of people in a position of power might exploit this opportunity to their advantage such as between organisations and employees where accessing ratings might be considered to be ‘in-contract,’ thus making it unavoidable to prevent the information to be used to influence things such as salary and promotion. As this effect would be very subtle, it cannot be guarded against, but can be mitigated through an open approach and awareness in general.

We consider the potential impacts of these in stage 3, starting with the impact on the services offered by F-social. Since the metric or rating would be seen as an important factor, its algorithm could be open to being gamed. When this information is exposed to the general public, it could lead to a huge backlash and negative repercussions. This effect might still take place even if the information might be partially true or completely false. Additionally, with the primary medium of such services being the web, any issue affecting the security and integrity of communication at this level also affects the service itself. Thus, attack vectors such as man-in-the-middle and DDoS would lead to disabling the service, which might lead to users being denied services. Based on the region and specitivity, this attack can be used to reject a particular subset of regions for political purposes. Methods such as ad-blockers and ISP injections (the practice of an ISP injecting or modifying packets) could be used to subvert the functioning of the service which might lead to unintended consequences for the users.

Some clients of the service may try to use the service for purposes that might not be acceptable from legal, business, ethical, or moral viewpoints. In such cases, it might be in F-social’s interest to try and vet their clients and access to the service which can further complicate consequences as they would effectively be denying information and business based on some agenda. This might or might not be acceptable based on how it is implemented, but usually, this leads to complicated terms and conditions that get more complex with time. The government or a state-level entity might want automatic-access to the data which might be an issue on several fronts. Based on the region and the political standing where this occurs, it may or may not lead to problems involving privacy. For example, in a more democratically open region, the potential backlash or political checks and balances present might mitigate the issue or subvert it using legislation to either deny access or grant it based on public opinion. In cases where the government is more isolated and practices authoritative governance, it is less likely to back down from its stance and might threaten to ban the service entirely unless it accepts the set terms.

Based on an understanding of the stakeholders involved, the functioning of the service, and how its potential effects on the behaviour, relations, and the service itself, we try to mitigate the impact of these through stage 4. Since F-social’s main issues of concern lie in its using the data to calculate the metric or rating, it is difficult if not impossible to ask it to stop providing the service as it this would constitute asking it to stop a legally acceptable practice. Instead, users or organisations might ask F-social to be more open about its usage of personal data, and take into consideration the ethical aspects of its usage. The algorithm used to calculate the rating could be requested to be openly evaluated to ensure that no bias is present and that it’s practices are legal. This can be done at several levels, from an internal committee tasked by F-social to a governmental enquiry. This would provide a level of authenticity and oversight to the usage of the data as well as prevent false information from spreading regarding the service.

On the aspect of preventing such usage of personal data altogether, the best possible way would be to disseminate a better and simpler understanding of the issues involved in the hopes to raise a public outcry about the practice and to get legislators involved to draft better laws protecting the concerns of its users. However, this approach has its weakness in the form of being bound by regions where political powers may not work in a cooperative manner. Thus, F-social may end up receiving patronage from one government while being completely banned by another. The medium of the web can be used extensively to share information towards the service and its ethical concerns, similar to existing organisations that concern privacy.

Conclusions

Users may not necessarily have total or absolute control over their data being used or collected. While progressive laws, particularly GDPR, specify several constraints and obligations over the use of persona data, the ultimate control lies with the data subject or the user. Even though consent is a mandatory affair, the responsibility of providing it correctly requires the user to first understand all the implications of the technology which is a difficult task. Instead, this responsibility can be shared by all parties involved, including the general community. Through this paper, we tried to discuss the implications of user-profiling and how it can be readily provided over the web as a service. We took the example of the episode Nosedive from Black Mirror to consider the ethical implications of such a service and developed a hypothetical scenario which tried to replicate the episode using existing technologies. To structure the discussion with a methodology, we used our tool, the Ethics Canvas, to understand the stakeholders involved, how the effects of the service on the behaviour and relations of stakeholders, and how the service may be used for unforeseen purposes. We concluded the discussion with a few action points addressing the issue of mitigating the ethical issues surrounding user-profiling.

Through this paper, we have hoped to present the argument that the technology itself should not form the basis of judgement over issues related to privacy, ethics, and morality. Rather, we need an open discussion involving the people who design and provide this technology, to identify such issues before the technology affects the general public. Such pragmatic discussions will lead to a better code of conduct, which may not be adopted into legislation immediately, but may be helpful in shaping the course of acceptable practices in the near future. One way to achieve this is through having an ethics-policy or an open approach to practising ethics towards responsible innovation. The ethics canvas is one such methodology and tool which encourages discussions in a manner that fit existing business practices. We envision such tools will help practitioners of responsible innovation communicate their good intentions to their intended users, for example, by publishing the ethics canvas for their service.

Acknowledgments

This paper is supported by the ADAPT Centre for Digital Content Technology, which is funded under the SFI Research Centres Programme (Grant 13/RC/2106) and is co-funded under the European Regional Development Fund.

The authors thank Wessel Reijers and other researchers involved in the development of the Ethics Canvas methodology.

References

An article by The Guardian on Facebook profiles being targeted for political ads http://reut.rs/2G2Zb2W↩︎

A notable example used at a large-scale in online ad auctions is US Patent US7552081B2↩︎

Analysis services provider Palantir accused of racial bias - New York Times (26 Sep 2016) http://nyti.ms/2EiGSX9↩︎

New York Times wrote a comprehensive article on the issues with Aadhar (21 Jan 2018) http://nyti.ms/2BnYceH↩︎

Ratings are from 0 to 5, with 5 being better or higher.↩︎

Smartphones are already available with biometric authentication methods such as facial recognition, iris scanning, and fingerprint detection.↩︎

Also known as Internet Service Provider or ISP↩︎