GDPR-driven Change Detection in Consent and Activity Metadata

Managing the Evolution and Preservation of the Data Web (MEPDaW) - co-located with Extended Semantic Web Conference (ESWC)

✍ Harshvardhan J. Pandit* , Declan O'Sullivan , Dave Lewis

Description: Proposing change-detection in processes to assess impact and compliance with GDPR

published version 🔓open-access archives: harshp.com , TARA , zenodo

📦resources: GDPR-driven Change Detection in Consent and Activity Metadata

Abstract This position paper explores changes concerning the relationship between consent and activities in context of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Detecting and recording such changes with their effects can provide assistance in demonstration and management of compliance. We present an approach for using metadata-driven change detection and representation towards supporting querying for GDPR compliance. We use P-Plan (an extension to PROV) for representing provenance of activities and ODRL for representing consent. We explore the presented approach by means of a use-case.

Introduction

Consent under the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)1 can be considered as an evolving entity based on the right to change or withdraw consent as well as the requirement to re-acquire consent upon certain changes in processing. In this paper, we explore this relationship between change in consent and the change in activities related to it. We consider consent as a set of permissions and prohibitions over activities that use the personal data, where the given consent provides the legal basis for their execution. We reuse the example use of ‘Sue’ [1], a data subject that uses a fitness tracking service for logging fitness activity. This service uses the given consent to send advertisements to the registered email, which is later withdrawn. This results in the consent representation reflecting this change, as well as a removing the corresponding activity from workflow.

The scope of this position paper is limited to identifying the relationship between changes in consent and activity metadata, along with approaches towards their detection and representation. The use-case provides an example for understanding the approach and the changes involved. We discuss these using P-Plan2 (an extension to PROV) to represent provenance of activities and ODRL to represent consent. This work provides a discussion on how this change can be detected and modeled, with potential applications in systems that assist in GDPR compliance.

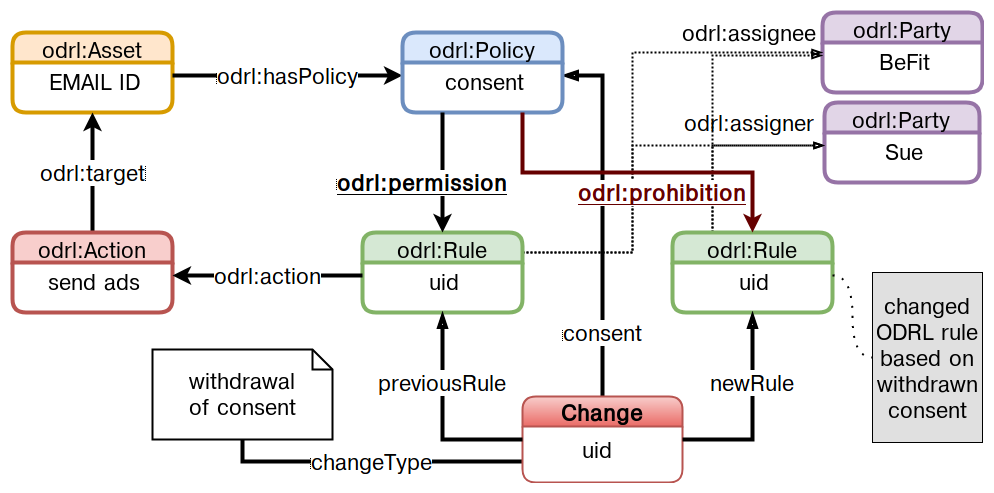

Change in consent

Using ODRL, each permission and prohibition (odrl:Rule) is expressed as an individual policy concerning the use of personal data (odrl:Asset) through an activity (odrl:Action). The changed consent in the case study, depicted3 in [fig:ODRL-consent], shows odrl:Rule being updated from odrl:permission to odrl:prohibition. Since each permission or prohibition within the consent is represented as a distinct odrl:Rule, once a policy is instantiated, its odrl:Asset (personal data) and odrl:Action (activity) will not change. Therefore, the Change object captures only the change type (withdrawal of consent) and change in rule from permit to prohibit. The captured change is useful in determining the effects of change in consent. In the case study, the change results in a prohibition over the activity of sending advertisements using email. This cause-effect relationship is further explored in Section 4.

Representing change in activities

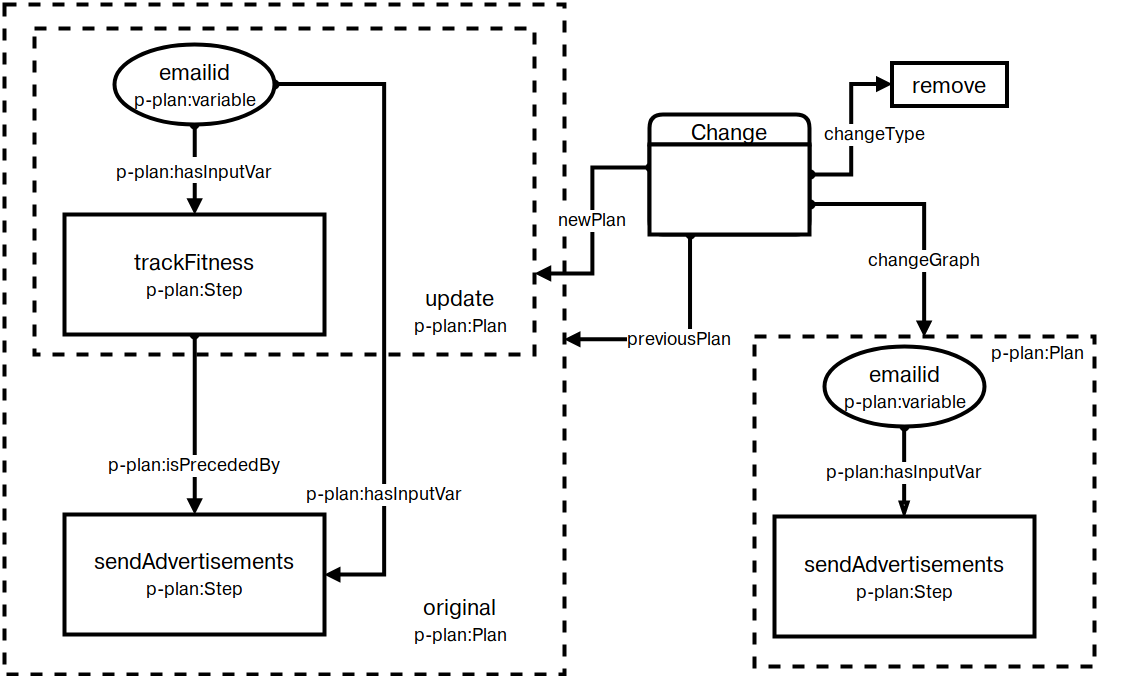

We use P-Plan, an extension of PROV since PROV represents things that have happened in the past, whereas P-Plan models the intent of what should happen. P-Plan acts as a template for workflows that are then used to capture executions using PROV, and provides a way to model interactions between activities, personal data, and consent at an abstract level. This approach for expression of consent and data metadata related to GDPR can be achieved using targeted vocabularies such as GDPRov [2]. for provenance and GDPRtEXT [3]. for compliance terms and concepts.

Detecting changes within activities (workflows) represented using p-plan:Plan is helpful to determine whether an updated consent is required from the data subject based as stipulated by GDPR requirements. [fig:activity]. depicts captured changes for the use case, where the step sendAdvertisements has been removed following changes in consent. The Change object links the original and updated workflows along with specifying the change type as ‘remove’ and a change graph containing differing elements in the two workflows. The task of change detection for workflows is considerably complex, and can be simplified by reducing the graph to simpler forms for easier analysis [4].

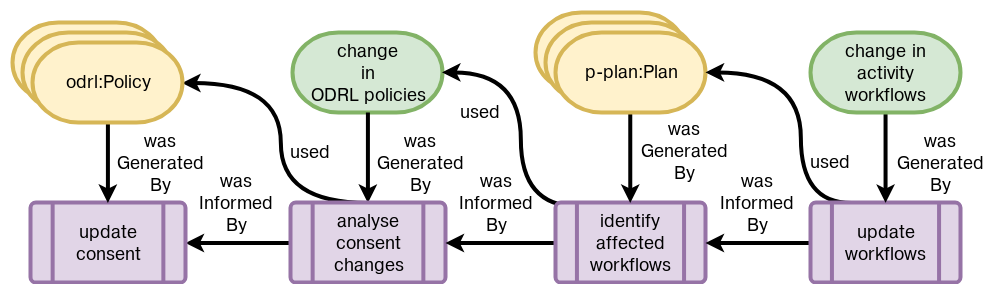

Linking the changes to enable compliance queries

Demonstrating changes in consent led to corresponding changes in activity workflows is part of compliance towards GDPR obligations. In the specified use-case, the withdrawal of consent resulted in a change in the ODRL policies representing consent, and led to a corresponding change in the activity workflows represented using P-Plan. This cause-effect relationship can be represented as a provenance trace as shown4 in [fig:provenance], and can act as documentation towards GDPR obligations. This can aid in the compliance process to demonstrate whether withdrawal of consent resulted in appropriate changes in workflows.

Conclusion & Future Work

This position paper discusses the detection and representation of changes in the context of consent and activities for GDPR compliance. The outlined approach deals with change within consent and activity metadata along with linking such changes in a cause-effect relationship. The approach discusses the use of ODRL for representing consent, with P-Plan (an extension of PROV) used to represent provenance of activities and workflows. A case study is used to explore and discuss the approach with a view towards documentation and demonstration of compliance.

In terms of potential future work, the change detection approach described in this paper can be used to automate processes associated with compliance, especially where a large number of data subjects are involved. A change in consent metadata is useful to identify its effects on the processing of personal data. As part of the compliance process, an individual’s provenance trace may need to be queried for all changes in given consent. By identifying and storing change in consent and activity metadata along with their provenance, it is possible to retrospectively demonstrate that such changes were accompanied by the necessary actions necessary to maintain compliance.

Ongoing compliance is a process mentioned in the GDPR where compliance is authoritatively assessed on an ongoing or periodical basis. Such assessments can be documented by linking them to a captured representation or a snapshot model of the system expressed as a workflow at that period of time. Such a workflow has the known state of being compliant based on the assessment. Future updates to the workflow may need a re-assessment of its compliance based on the changes introduced in the update. A change detection approach for such workflows can be optimised to highlight only those changes that are relevant to the compliance obligations, such as the use of personal data within activities.

Linking changes between ‘events’ such as change in consent and change in activity workflows, it is possible to create a system that can perform a ‘self-check’ analysis for compliance based on whether expected activities occur upon detection of certain changes. This can automate the process of compliance analysis on graphs which contain a large number of data subjects where it is not possible to manually investigate the effects and behaviour of each individual change in given consent and activities. The automated system can analyse the provenance logs to ensure that the required changes have correctly occurred, and can be used to detect and alert for situations where manual intervention is required to ensure compliance.

It is possible that the approach may not be scalable where a large amount of metadata is generated. In such cases, the approach is still useful as a mechanism to demonstrate that required behaviour takes place within a model of the system.

Acknowledgements

This paper is supported by the ADAPT Centre for Digital Content Technology, which is funded under the SFI Research Centres Programme (Grant 13/RC/2106) and is co-funded under the European Regional Development Fund.

References

http://purl.org/adaptcentre/openscience/resources/GDPRtEXT#article4-11↩︎

Using diagram structures and colours from ODRL’s documentation↩︎

Arrows use same notation as PROV to depict information flow↩︎