Extracting Provenance Metadata from Privacy Policies

International Provenance and Annotation Workshop (IPAW)

✍ Harshvardhan J. Pandit* , Declan O'Sullivan , Dave Lewis

Description: Discussing how information about data provenance can be extracted from privacy policies and modelled in semantic web

published version 🔓open-access archives: harshp.com , TARA , zenodo

📦resources: poster , Extracting Provenance Metadata from Privacy Policies

Abstract Privacy policies are legal documents that describe activities over personal data such as its collection, usage, processing, sharing, and storage. Expressing this information as provenance metadata can aid in legal accountability as well as modelling of data usage in real-world use-cases. In this paper, we describe our early work on identification, extraction, and representation of provenance information within privacy policies. We discuss the adoption of entity extraction approaches using concepts and keywords defined by the GDPRtEXT resource along with using annotated privacy policy corpus from the UsablePrivacy project. We use the previously published GDPRov ontology (an extension of PROV-O) to model provenance model extracted from privacy policies.

Motivation

A privacy policy is a document that outlines information about activities related to personal data, and are notoriously difficult to read [1]. The privacy policy (along with T&C and other documents) is commonly the only available authoritative indication of how personal data is collected and used. Legislations, such as the upcoming General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), influence what information is required to be mentioned in the privacy policy, but do not provide a uniform structure or mechanism for its declaration.

Research, especially related to technical modelling of privacy, therefore suffers from a lack of structured information about real-world usage of personal data. The UsablePrivacy Project [2] provides a semi-automated annotation of privacy policy based on a combination of crowdsourcing, machine learning and natural language processing. It annotates privacy policy statements to help users identify different data collection and use practices. We propose to extend this approach to identify and automatically extract provenance metadata from privacy policies. This paper describes provenance information present in privacy policies along with approaches towards its identification, extraction, and representation.

Provenance Metadata

Identification

GDPR is poised to significantly change the type of information made available to the data subject or user regarding activities over their personal data. We discuss identification of provenance metadata using the privacy policy provided by Airbnb Ireland1, and focus on categories or types of personal data, along with descriptions of activities that relate to how it is collected, used, shared, and stored. The policy contains sections that offer context to its contents. For example, the title of Section 1 refers to collection of information with subsections describing where the information is obtained from. Taking into account such context can be helpful towards heuristics for eventual extraction of provenance metadata. For example, section 1.1 describes personal information provided when creating a new account. Combining this with the aforementioned context, we can infer that account information is a data category with first name, last name, email address, date of birth being its types; and sign-up is an activity that collects account information direct from the user.

Extraction using Keyword-based entity recognition

Manual efforts to extract this provenance information do not scale well across a large number of policies, nor can they be automated. Entity extraction techniques [3], [4] can help in identification and categorisation of methods. Identification and extraction can take place by searching for certain keywords known to refer to provenance information. For example, the word “collect” is almost always accompanied with the type of information collected. A starting point for GDPR relevant keywords is the GDPRtEXT ontology [5] that defines GDPR terms and concepts using the SKOS vocabulary.

Extraction using Machine learning models

This approach is similar to the one take by the UsablePrivacy project [2] and requires annotations over a sample corpus to train a machine learning algorithm for automatic entity recognition and extraction. We plan to expand upon the categorisation of privacy policy statements based on published approaches [2], [6] with our keyword-based extraction method. For this, the categorisation of statements can be used to identify the type of information contained within the statement. For example, a statement annotated with “First Party Collection/Use” offers the context of a data collection activity, which can be used by the extraction algorithm to identify the contextually relevant terms. Therefore, it may be more performant to train the entity extraction algorithm only on similarly categorised statements as opposed to all statements within policies.

Representation

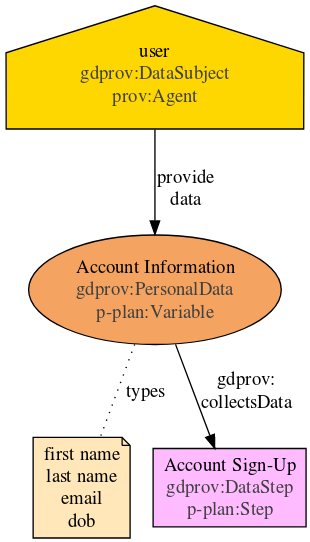

Provenance metadata expressed using PROV-O concepts are assertions about the past (execution) and should not be used to depict a ‘model’ or abstraction of how things are supposed to be happen. To this end, we created GDPRov [7], an OWL2 ontology that extends PROV-O and P-Plan (an extension of PROV-O) for modelling data-flows involving consent and data using relevant GDPR terminology. An example representation of the use-case is depicted in Fig 1 with its representation as RDF triples.

:User

a gdprov:DataSubject,

prov:Agent .

:AccountInformation

rdfs:subClassOf gdprov:PersonalData .

:FirstName a :AccountInformation .

:LastName a :AccountInformation .

:Email a :AccountInformation .

:DOB a :AccountInformation .

:AccountSignUp

a gdprov:DataStep ;

dct:source :User ;

gdprov:collectsData :AccountInformation ;

gdprov:hasLegalBasis

gdprtext:LegitimateInterest .Listing Example use-case for representation of information in Airbnb Privacy Policy

Potential Applications

Easier representation of privacy policies

Privacy policies, as described earlier, have been notoriously difficult to interpret and understand from the point of view of a generic data subject or user. Efforts such as tl;drLegal3 and UsablePrivacy are good examples of community efforts to mitigate this problem, with UsablePrivacy offering a semi-automated way to annotate privacy policies. Provenance metadata extracted from a privacy policy can be used to augment these efforts through better descriptions and visualisations of how the data is used across different processes. Having a visual representation accompany privacy policies can help users in quickly grasping the gist of the policy.

Approaches related to privacy preferences

Matching a user’s privacy preferences with the service is an important topic given the increasing misuse of personal data and the lack of readily available information about data practices. Provenance metadata can augment approaches that try to solve this problem by providing a description of how data is used by the target entity related to the policy. One possibility towards this is using the provenance metadata towards interpreting privacy policies as agreements using Open Digital Rights Language (ODRL). The provenance metadata provides information about what data is collected, how it is used, where/when it is shared. By matching the user’s privacy preferences (also expressed as ODRL) with the ODRL privacy policy, it could be possible to express areas that need user attention or those that do not comply with the user’s preferences.

Conclusion

Through this paper, we presented our early stage work for the identification, extraction, and representation of provenance metadata present in privacy policies. We describe our approach that uses keyword-based entity extraction based on GDPR terms and concepts provided by the GDPRtEXT resource. This approach adopts the machine-learning model used by the UsablePrivacy project to create annotated privacy policies. We represent the extracted provenance metadata using GDPRov, which extends PROV-O and P-Plan, and allows for an abstract model of the policy to be represented. We describe the potential application of this work to augment several important topics related to privacy and data practices.

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the ADAPT Centre for Digital Content Technology which is funded under the SFI Research Centres Programme (Grant 13/RC/2106) and is co-funded under the European Regional Development Fund.

References

accessed 16-APR-2018 https://www.airbnb.ie/terms/privacy_policy.↩︎