Towards Generating Policy-compliant Datasets

International Conference on Semantic Computing (ICSC)

✍ Christophe Debruyne* , Harshvardhan J. Pandit , Declan O'Sullivan , Dave Lewis

Description: Creating datasets that are inherently compliant with consent under GDPR

published version 🔓open-access archives: harshp.com , TARA , zenodo

📦resources: repo , Towards Generating Policy-compliant Datasets

Abstract The development of intelligent (e.g., AI-based) applications increasingly requires governance models and processes, as financial legal sanctions are more and more being associated with violation of policies. We propose an ontology representing the informed consent that was collected by an organization and argue how it can be used to assess a dataset prior its use in any type of data processing activities. We demonstrate the utility of our ontology using a particular scenario, where datasets are generated “just in time” for a particular purpose such as sending newsletters. This scenario shows how data processing activities can be managed to in such a way as to support compliance verification. This paper furthermore compares the contributions to related work and positions it into prior work concerned with the broader problem of prescribing and analyzing compliance.

Keywords component; Governance, Consent Representation, Compliance Analysis, Semantic Mappings

Introduction

While various scientific communities aim to improve the accuracy and efficiency of intelligent system, one must not forget the ethical and legal considerations of data processing. Data processing in general is increasingly the subject of various regulations such as the General Data Protection Regulation1 (GDPR). Such initiatives spur the investment of means and resources in novel ways for facilitating compliance verification [1]. Prior work looked into: the representation of GDPR as a Linked Data resource which one can refer to and engage with [2]; a proposal for open, semantic vocabularies to represent various actors and interactions [1]2 (based on PROV-O [3]), a provenance ontology, to facilitate compliance checking; and, a simple model for representing informed consent [4].

Semantic technologies facilitate interoperability, transparency and traceability, which provided the motivation for the adoption of these technologies in abovementioned prior work. While prior work has aimed to tackle the problems of representing a piece of legislation, the various interactions between stakeholders and representing informed consent, we have yet to investigate the problem of rendering this information actionable: “How can one engage with the informed consent that an organization has collected (i.e., a priori) while commencing a data processing activity?” We present a model for representing consent and its changes over time. This is useful for creating or assessing the compliance of datasets. The problem we address is the generation of datasets “just in time” that are compliant with certain regulations such as GDPR based on consent information. Both model and approach constitute the contributions of this paper.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 presents our model and its rationale; Section 3 briefly discusses the implementation of our model in OWL; Section 4 highlights the differences of this model and our prior work, which also explains why they are complementary; Section 5 demonstrates how our model can be used to assess a dataset prior to data processing; Section 6 discusses related work; and finally, Section 7 concludes our paper and presents future work.

The Model

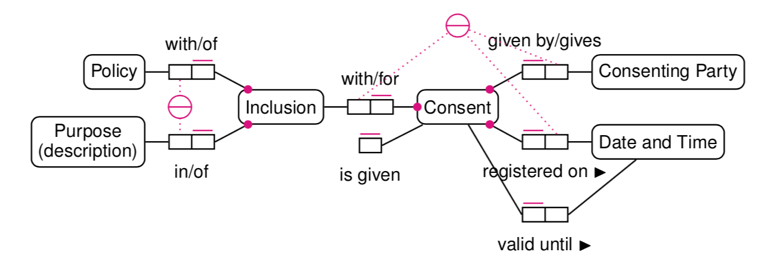

The model we propose in this paper is a revision of a model proposed in [4] to demonstrate the use of semantic technologies for engaging with the informed consent that an organization has collected. While fit for the purpose for the sake of the demonstrator reported, the model in [5] has several shortcomings; there is an apparent disconnect between various classes (lack of context) and there is no explicit notion that policies (or terms and conditions) and consent will evolve over time. With those limitations in mind, we propose a new model. We used Object Role Modelling (ORM) [5] to formalize the model (see Fig. 1).

Unlike UML class diagrams, where classes can have attributes and associations, ORM is a fact-oriented approach where all relations between object-types (i.e. “classes”) are expressed in a similar fashion. In Fig. 1, all relations are binary, which means there are two roles (represented by the smaller rectangles) for each relation. Each role can only be played by exactly one object-type. We will now describe the different concepts and the constraints on their roles (depicted in magenta).

Policy and Purpose

Policy is an abstract concept for representing things such as Terms and Conditions, Data Privacy Policies, etc. All of which encompass various notions of user rights, user obligations and what a service intends to do with the data.

Purpose is a concept for representing the purpose of using (personal) data. This may range from using email addresses to send a newsletter to using one’s profile and purchase history for targeted advertising. While policies may change over time, a purpose does not. Any change in the description of a purpose results in a new purpose. One can thus see “description” as the conceptual identifier for purposes.

Inclusion represents the relation between a policy and a purpose. Note that the roles that Inclusion plays with Policy and Purpose are both mandatory (represented by the dot) and unique (represented by the line above the role box). While an inclusion must have exactly 1 policy and must have exactly one purpose, a policy may have 1 or more inclusions and a purpose may be the subject of one or more inclusions. The external uniqueness constraint (a circle with a line) connects all the roles that identify an instance of an object type. Here, each combination of a policy and a purpose identifies an inclusion.

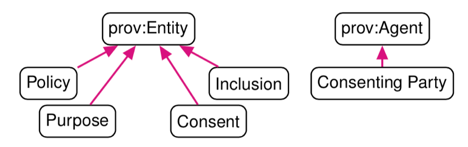

Our model reuses the provenance ontology PROV-O [3] (Fig. 1 - bottom) by specializing some of its concepts. We state policy, purpose, inclusion and consent to be subtypes of prov:Entity, which allows us to reuse predicates such as prov:wasRevisionOf. Relating revisions of entities with prov:wasRevisionOf allows us to formulate a query returning all parties who have not yet given their consent to a revision of a policy.

Consent

Consent represents the result of a consenting party reacting to a consent request (which may be requested by means of a form). As consent needs to be informed and explicit, we ideally capture the consent as a "yes" or a "no". Note the unary role “is given” that Consent can play. When an instance of Consent plays that role, then consent was given. When an instance of consent exists and does not play that role, then that means the consenting party has not given the permission for their data to be used for a particular purpose.

The absence of a consent instance, if that were to happen, is interpreted as a "no". Treating the absence of information as being false3 information corresponds roughly to a closed world interpretation of the data.Consenting Party is used to represent a person, or an agent acting on behalf of someone giving their consent for the purposes that are included in a policy. Such agents can be natural and legal persons. For the purpose of our model, a consent is given by only one consenting party.

Date and Time are used to represent when consent was given. Together with the inclusion for which a consent needs to be captured and the consenting party, the three attributes are used to identify an instance of consent. By including the date and time on which it was captured, we can easily store and process information in case consent needs to be requested on regular interval.

Again, the concepts we introduced in this section specialize classes in PROV-O. A consenting party corresponds with prov:Agent, and consent is a specialization of prov:Entity. The latter allows one to represent revisions of consent if that were to take place (e.g., opting out).

Implementation and Use of the Ontology

ORM diagrams can be mapped onto OWL [6] and as such provide a convenient way for modelling prior to implementing ontologies. The implementation of our ontology4 was informed by the mapping from ORM to OWL by [6]. Note that all instances of our classes will be identified by a URI, but that the external uniqueness constraints (representing conceptual identifiers) are implemented as axioms. This might lead a reasoner that two instances of an inclusion are deemed the same (owl:sameAs) when they have values for the same identifying attributes. One way to avoid this is to assert owl:differentFrom statements, which in turn would lead to a contradiction if such two inclusions were to exist. Our approach to validating a knowledge base is the adoption of the SHACL Shapes Constraint Language [7], which is a W3C Recommendation for prescribing valid RDF graphs. SHACL is especially useful for cardinality constraints, which are the key constraints in our conceptual model.

The object types in Fig. 1 (top) have been implemented as instances of owl:Class. These classes extend PROV-O as per Fig. 1 (bottom). The relations with Date and Time and the unary role “is given”' are implemented as datatype properties with xsd:dateTime and xsd:boolean as a range respectively. All other relations have been implemented as two object properties with one being the owl:inverseOf of the other. In the ontology, we have stated that the classes are all disjoint. As PROV-O has prov:Person and prov:Organization as subclasses of prov:Agent, we also added an axiom stating that ont:Consenting_Party is equivalent with the concept-union of these two PROV-O classes.

Generating compliant datasets

In this section, we will demonstrate our approach by 1) describing how we use a knowledge base using the ontology we presented in the previous section; 2) explain how we generate R2RML [8] mappings for generating datasets based on prior work; and 3) how we combine 1) and 2) to generate a consent-compliant dataset for use in data processing operations.

Using the Consent Ontology

As we had no access to a suitable evolving dataset, we had to create one ourselves in order to demonstrate our approach. The algorithm for generating the synthetic dataset is outlined in Appendix A. The algorithm generated a dataset involving 5 systems, each with a policy that included 3 of 10 purposes. A subset of 10 users were randomly assigned to 1 or 2 systems. After 100 iterations: a) the policies of systems #4 and #5 were updated twice, and that of system #2 only once; b) users renewed their given consent 29 times; c) users withdrew their given consent 68 times; d) and users gave their consent which was previously renewed 102 times; e) users gave their consent to an inclusion that was initially not given 16 times.5

Using the ontology we present in this paper, we can retrieve consent information of a particular purpose of the latest version of a policy as follows:

DESCRIBE ?consent WHERE {

?consent ont:forInclusion ?inclusion .

{ # GET THE LATEST INCLUSION FOR A POLICY

SELECT ?inclusion WHERE {

?inclusion ont:ofPurpose <.../purpose> .

?inclusion ont:ofPolicy <.../policy> .

<.../policy> dcterms:created ?dt .

} ORDER BY DESC(?dt) LIMIT 1 }

?consent ont:givenBy ?user .

?consent ont:registeredOn ?datetime .

# GET THE LATEST CONSENT FOR EACH USER BY FILTERING

# THOSE THAT HAVE BEEN SUCCEEDED BY ANOTHER CONSENT

FILTER NOT EXISTS {

[ ont:forInclusion ?inclusion ;

ont:givenBy ?user ;

ont:registeredOn ?datetime2 ]

FILTER(?datetime2 > ?datetime) } }Listing 1: Retrieving consent information for a purpose and policy. All consent information is returned by the DESCRIBE query. The query first looks for the latest inclusion a system. The second part of the query seeks the latest consent information for each user. For brevity, we ommitted prefixes, and use <.../purpose> and <.../policy> for IRIs of a purpose and a policy

Line 2 matches with consent information and their inclusions. The inclusions are then limited to the most recent inclusion for a particular purpose and policy. We also have to search for most recent consent information for each user by removing those for which there is a consent with a more recent date. A reader may notice that we did not filter on the status of a consent (given or not), this is due to the fact that the most recent consent information might be about withdrawing a consent. We can encapsulate the query (starting from the WHERE clause) as a subquery and subsequently filter those for which consent has been given and that are not expired. This will allow us to compile a list of people who have given their consent later on.

Generating R2RML Mappings for Datasets

The study in [9] proposed a method for generating an executable R2RML [8] file based on a data structure definitions (DSD) using the RDF Data Cube Vocabulary [10]. DSDs can be regarded as a schema for datasets, which are represented in RDF. In [9], the authors presented an approach in which DSDs were annotated so that a sequence of SPARQL CONSTRUCT queries generates an R2RML mapping for generating a dataset according to that DSD. In this paper we relate DSDs with purposes.

Using the synthetic dataset previously mentioned, we use a simple Data Structure Definition (see Listing 2). We see in this listing that this DSD retrieves data from a table and that the values for the dimension and measure are obtained from columns. Those values are used to create IRIs, one to identify observations (or “records”) and one for mailboxes (according to the FOAF vocabulary). We note that the DSD is annotated for a particular purpose and system (in this case one of each).

# PREFIXES OMMITED FOR BREVITY

@base <http://www.example.org/>

dct:identifier a rdf:Property, qb:DimensionProperty ;

rr:template "http://data.example.com/user/{id}" ;

rdfs:label "user id"@en ;

rdfs:subPropertyOf sdmx-dimension:refPeriod ;

rdfs:range owl:Thing .

foaf:mbox a rdf:Property, qb:MeasureProperty ;

rr:template "mailto:{email}" ;

rdfs:label "email address"@en ;

rdfs:subPropertyOf sdmx-measure:obsValue ;

rdfs:range owl:Thing .

<#dsd-le> a qb:DataStructureDefinition;

rr:tableName "user";

ont:forPurpose <http://data.example.com/purpose/8> ;

ont:forPolicy <http://data.example.com/policy/10> ;

qb:component [ qb:dimension dct:identifier ];

qb:component [ qb:measure foaf:mbox ] .Listing 2: A data structure definition where each observation (~ “record”) is identified by a user and the value is the email address.

We note that the approach in [9] describes that the graphs for the DSD and the annotations are kept separate. Lines 4, 9, and 14 of Listing 2 would be stored separately and “merged” for the creation of the R2RML mapping. This allows one to reuse DSDs for various data sources, purposes, etc.

The R2RML mapping that is the result of executing a sequence of CONSTRUCT queries as outlined in [9] is shown in Listing 3. The triples map retrieves data from the table “user”. The subject map informs the R2RML engine that instances of qb:Observation will be created from that table. The columns of all dimensions in the DSD are used to generate a template in that subject map. That template will generate identifiers for each observation. Each observation will be linked to the generated dataset using the predicate object map in lines 10 to 11. We have omitted the full URI for brevity (yellow), but is based on the table or query and the base of the DSD. Finally, predicate object maps are generated for each dimension and measure in the DSD.

[ rr:logicalTable [ rr:tableName "user" ] ;

rr:predicateObjectMap [

rr:objectMap [

rr:template "http://data.example.com/user/{id}" ] ;

rr:predicate dct:identifier ] ;

rr:predicateObjectMap [

rr:objectMap [ rr:template "mailto:{email}" ] ;

rr:predicate foaf:mbox ] ;

rr:predicateObjectMap [

rr:object <uri-for-dataset> ;

rr:predicate qb:dataset ] ;

rr:subjectMap [

rr:class qb:Observation ;

rr:template "{id}" ;

rr:termType rr:BlankNode ] ] .Listing 3: Generated R2RML Dataset – prefixes ommitted for brevity

Creating a Compliant Dataset

The synthetic dataset contains, for purpose #8 and policy #10, consent information about 3 users. These 3 users have engaged several times with the policies and inclusions during the 100 iterations. In the “end”, user #10 has accepted the inclusion whereas users #8 and #9 have withdrawn their consent. The execution of the R2RML mapping would result in a dataset that contains all users, but we have to filter out only those for which we have an explicit consent. While we could manipulate the source of the DSD by creating an SQL query with necessary WHERE clauses, we choose to use SPARQL for creating a dataset that is compliant. This approach allows us not only to cache intermediate outputs, but also allows us to avail of R2RML dialects that support non-relational data, e.g. [11]. I.e., we become less dependent on the underlying database technology.

With the query in Listing 1 we fetch the latest consent information of users. This information is used to construct a list of users that have given their consent. That list is then used to create and execute a SPARQL DESCRIBE query returning to us the dataset fit for that policy’s purpose. The list is used to create a VALUES clause. The query is shown in Listing 4 and is applied to the generated dataset to obtain a subset with only the information of those that have given their consent.

PREFIX qb: <http://purl.org/linked-data/cube#>

PREFIX dct: <http://purl.org/dc/terms/>

DESCRIBE ?obs ?dataset WHERE {

?obs a qb:Observation .

?obs qb:dataSet ?dataset .

?obs dct:identifier ?dim .

VALUES ?dim { <http://data.example.com/user/10> } }Listing 4: Obtaining a subset of the generated dataset that contains only the information of those who have given consent.

Note that the predicate in Listing 4 corresponds with the predicate of the DSD’s dimension in Listing 2. The dimensions are used to identify observations and can be an arbitrary IRI. We inspect the DSD to obtain those when creating the DESCRIBE query. When dealing with so-called “multi-measure” observations – where a dataset has multiple values per dimension (e.g., last name, first name, etc.), the Data Cube Recommendation prescribes “splitting” the information in multiple observations (with the same dimensions) for each value. The query listed above still functions in those cases.

We already stated for this particular purpose and policy, user #10 has accepted the inclusion and users #8 and #9 have withdrawn their consent. This corresponds with the result of executing the query of Listing 4 shown below.

@prefix qb: <http://purl.org/linked-data/cube#> .

@prefix dct: <http://purl.org/dc/terms/> .

@prefix foaf: <http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/> .

<uri-for-dataset>

a qb:DataSet ;

qb:structure <http://www.example.org/#dsd-le> .

[ a qb:Observation ;

dct:identifier <http://data.example.com/user/10> ;

qb:dataSet <uri-for-dataset> ;

foaf:mbox <mailto:[email protected]> ] .Listing 5: Resulting compliant dataset after executing the SPARQL DESCRIBE query of Listing 4. Note that the URI of the dataset corresponds with that of the constant in Listing 3

Discussion

Implementation

The implementation has been developed as a service. We assume that one maps the consent information stored in some non-RDF format to our consent ontology (e.g., using R2RML) and exposes that information via a SPARQL endpoint. Tools such as Ontop [12] allow one to access relational databases with SPARQL via an R2RML mapping. Important to note is that both the service and SPARQL endpoint are residing on a server and that the endpoint is not accessible from outside the system – which is usually the case for any databases in an organizational setting. One just needs an annotated DSD and a link to a purpose and policy to obtain the filtered dataset for a particular data processing activity. We note that any governance activities related to creating the DSD as well as the use of the obtained dataset are outside the scope of this study, which brings us to this paper’s relation with prior work.

Relation with prior work

The work presented in [1] is, in short, focused on adopting Semantic Web technologies and extending standardized vocabularies for 1) prescribing the actions that should take place as well as the interactions between various stakeholders in the context of GDPR, and 2) analyze these models with respect to annotated logs and questionnaires to facilitate compliance verification. [1] is from a prescriptive level concerned with the datasets that data processing activities use, who and how consent was obtained, and whether data processing activities comply with the informed consent that is and will be collected.

While there is an overlap in terminology and the application domain, the model we propose in this paper is to allow agents to engage with informed consent that has already been collected by an organization and is not concerned how consent should look like nor how it was obtained. The model we propose in this paper is not intended for compliance verification purposes, but to 1) assess potential issues regarding compliance with a dataset prior to data processing and 2) is useful for generating a dataset taking into account informed consent. Though there are some nuances in the interpretation of some terminology used in both studies, they are complementary in a broader narrative. Future work will investigate how both vocabularies align.

Related Work

SPIRIT [13] is a platform for ingesting and analyzing transaction logs for transparency and compliance checking. SPIRIT uses semantic technologies to verify that all business processes comply with both the consent provided by a person and the relevant obligations from GDPR. Their work encodes the consent collected in the past and has a representation for purposes. In [14], the authors demonstrated the SPECIAL consent, transparency and compliance system. They also used RDF for representing concepts such as purpose. Their model allows one to represent what a user shares with others and how it may be used. They then avail of “OWL reasoning to verify whether the authorized operations specified by a data subject through their given consent, subsume the specific data processing records in the transparency log.” [14]

Both studies have models for similar concept (data subject -- or the person, purpose, etc.). And both studies aim to analyze compliance based on logs (thus a posteriori) and to present the results of that analysis in a dashboard. Our goal, however, is to aid one obtaining a dataset that is compliant for certain data processes purposes “just in time”.

The vocabularies in these studies and the work presented in [15] have classes for representing data processing activities (provenance) as well as a more fine-grained representation for the data that people wanted to share. In this study, it sufficed to model the relationship between consent, purpose and dataset. More fine-grained representations for the data that a person agrees to share for a particular purpose can be obtained by qualifying the purposes with the data.

While our study tackles a different problem, this paper and the references in this section all fit the broader narrative around compliance governance.

Conclusions

We tried to tackle the problem of generating datasets “just in time” that are compliant with certain regulations such as GDPR. One important aspect of GDPR, which can also be found in other policies and legislations, is informed consent. In order to generate these datasets, we developed a novel model for representing consent information that have been collected.

We argued that related work is more focused on compliance verification of prescriptive models whereas our model would be used to generate a dataset for a particular data processing purpose. A novel aspect of our model is the concept between purpose, policy, consent and consenting party: “Inclusion”, allowing us to represent (changes in) consent over time. We described how this model can be used to retrieve all consenting parties to generate compliant datasets for particular data processing purposes. We demonstrated our approach with a synthetic dataset that has been made available.

A limitation of our study is the type of evaluation of our approach; a demonstration using synthetic data. A detailed case study may address this limitation. Future work also includes the integration of our models with the work presented in [1].

Acknowledgements The ADAPT Centre for Digital Content Technology is funded under the SFI Research Centres Programme (Grant 13/RC/2106) and is co-funded under the European Regional Development Fund.

References

[1] H. J. Pandit, D. O’Sullivan, and D. Lewis, “Queryable Provenance Metadata For GDPR Compliance,” in Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Semantic Systems (SEMANTiCS 2018), Vienna, Austria, Sep. 10-13, 2018, 2018, pp. 262–268.

[2] H. J. Pandit, K. Fatema, D. O’Sullivan, and D. Lewis, “GDPRtEXT - GDPR as a Linked Data Resource,” in The Semantic Web - 15th International Conference, ESWC 2018, Heraklion, Crete, Greece, June 3-7, 2018, Proceedings, 2018, vol. 10843, pp. 481–495.

[3] T. Lebo, D. McGuinness, and S. Sahoo, “PROV-O: The PROV Ontology,” 2013. [Online]. Available: https://www.w3.org/TR/prov-o/.

[4] K. Fatema, E. Hadziselimovic, H. J. Pandit, C. Debruyne, D. Lewis, and D. O’Sullivan, “Compliance through informed consent: Semantic based consent permission and data management model,” in CEUR Workshop Proceedings, 2017, vol. 1951.

[5] T. A. Halpin and T. Morgan, Information modeling and relational databases (2. ed.). Morgan Kaufmann, 2008.

[6] E. Franconi, A. Mosca, and D. Solomakhin, “ORM2 Encoding into Description Logic (Extended Abstract),” in Proceedings of the 2012 International Workshop on Description Logics, DL-2012, Rome, Italy, June 7-10, 2012, 2012, vol. 846.

[7] H. Knublauch and D. Kontokostas, “Shapes Constraint Language (SHACL),” W3C, 2017. [Online]. Available: https://www.w3.org/TR/shacl/.

[8] S. Das, R. Cyganiak, and S. Sundara, “R2RML: RDB to RDF Mapping Language,” 2012. [Online]. Available: https://www.w3.org/TR/r2rml/.

[9] C. Debruyne, D. Lewis, and D. O’Sullivan, “Generating Executable Mappings from RDF Data Cube Data Structure Definitions,” in On the Move to Meaningful Internet Systems: OTM 2018 Conferences - Confederated International Conferences: CoopIS, CT&C, and ODBASE 2018, Valletta, Malta, October 22-26, 2018. Proceedings, 2018, vol. 11230, pp. 333–350.

[10] R. Cyganiak and D. Reynolds, “The RDF Data Cube Vocabulary,” 2014. [Online]. Available: https://www.w3.org/TR/vocab-data-cube/.

[11] A. Dimou, M. Vander Sande, P. Colpaert, R. Verborgh, E. Mannens, and R. Van de Walle, “RML: A Generic Language for Integrated RDF Mappings of Heterogeneous Data,” in Proceedings of the Workshop on Linked Data on the Web co-located with the 23rd International World Wide Web Conference (WWW 2014), Seoul, Korea, April 8, 2014., 2014, vol. 1184.

[12] D. Calvanese et al., “Ontop: Answering SPARQL queries over relational databases,” Semant. Web, vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 471–487, 2017.

[13] P. Westphal, J. D. Fernández, S. Kirrane, and J. Lehmann, “SPIRIT: A Semantic Transparency and Compliance Stack,” in Proceedings of the Posters and Demos Track of the 14th International Conference on Semantic Systems co-located with the 14th International Conference on Semantic Systems (SEMANTiCS 2018), Vienna, Austria, September 10-13, 2018., 2018, vol. 2198.

[14] S. Kirrane et al., “A Scalable Consent, Transparency and Compliance Architecture,” in The Semantic Web: ESWC 2018 Satellite Events - ESWC 2018 Satellite Events, Heraklion, Crete, Greece, June 3-7, 2018, Revised Selected Papers, 2018, vol. 11155, pp. 131–136.

[15] J. Lehmann et al., “Distributed Semantic Analytics Using the SANSA Stack,” in The Semantic Web - ISWC 2017 - 16th International Semantic Web Conference, Vienna, Austria, October 21-25, 2017, Proceedings, Part II, 2017, vol. 10588, pp. 147–155.

Appendix

Creating a Synthetic Dataset

The synthetic data is created using a list of 10 users, 10 purposes, and 5 systems. Whenever a user gives their consent for a purpose, it is valid for 30 days. There are 100 iterations and with each iteration, 3 days pass by. Prior to iterating: i) each system's policy will be assigned a random 30% of the purposes; ii) 70% of the users will accept 50% of the policies; iii) of those 70%, each user has a 50% chance of accepting all inclusions of that policy, or only half of them. We note that all numbers are rounded down. We note that all numbers can be configured. For this study, the numbers were arbitrary chosen to ensure that there was some variety in the dataset. We are not aware of any literature that provides realistic probabilities for each scenario.

With each iteration, we add 3 days to the start date of our simulation. Each policy has furthermore 1% chance of being updated, which means that one purpose is deleted, and one different purpose is added. For all users that have agreed to a purpose of that policy, there is a 50% chance they accept all inclusions of the updated policy, otherwise they only accept half of the inclusions. Then, for each policy p we look at the users that have accepted 1 or more of the policy's inclusions. For each user u and each inclusion i of p, we check whether there is consent information c: a) If there is no c -- the user has not yet given consent for that inclusion -- there is a 5% chance of giving consent; b) If there is a given consent that is expired, there is a 50% chance of the user renewing their consent; c) Otherwise there is a 5% chance of a user changing their mind on their consent; withdrawing a given consent, or giving their consent on a previously retracted consent.

https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2016/679/oj↩︎

http://openscience.adaptcentre.ie/projects/CDMM/GDPRov/↩︎

As in “not true” instead of “incorrect”.↩︎

http://openscience.adaptcentre.ie/ontologies/consent-mapping-jit/ontology↩︎

Dataset available at https://scss.tcd.ie/~debruync/icsc2019/↩︎