Towards Cataloguing Potential Derivations of Personal Data

Extended Semantic Web Conference (ESWC)

✍ Harshvardhan J. Pandit* , Javier Fernandez , Christophe Debruyne , Axel Polleres

Description: Creating a catalogue of data derivations or inferences in literature and building a semantic-web rule-based system for identifying potential derivations

published version 🔓open-access archives: harshp.com , TARA , zenodo

📦resources: repo , Towards Cataloguing Potential Derivations of Personal Data

Abstract The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) has established transparency and accountability in the context of personal data usage and collection. While its obligations clearly apply to data explicitly obtained from data subjects, the situation is less clear for data derived from existing personal data. In this paper, we address this issue with an approach for identifying potential data derivations using a rule-based formalisation of examples documented in the literature using Semantic Web standards. Our approach is useful for identifying risks of potential data derivations from given data and provides a starting point towards an open catalogue to document known derivations for the privacy community, but also for data controllers, in order to raise awareness in which sense their data collections could become problematic.

Keywords personal data, derived data, GDPR, Semantic Web

Introduction

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) [1] provides several obligations that require transparency regarding collection and processing of personal data. Compliance towards these obligations requires data controllers to explain the processing of data and its purpose in understandable terms, such as through privacy policies, where it is made clear which categories of personal data are collected, and for which purpose. However, these categories are limited to data collected from the data subject and do not contain information on data derived from collected data. Thus, data subjects are often left unclear about the nature and usage of their personal data, which is still not described explicitly in terms of derived and potentially sensitive features. A well-known example of this is inferring personality types and political opinions from social media interactions [2]. Likewise, even good-willing data controllers may not be aware of what additional data can be inferred from data they collect.

In this paper we propose to address the issue of understanding risks about potential derivations of additional information from collected personal data by making these derivations explicit and machine-readable. We collect examples of derivations from literature and formalise them as machine-readable inference rules using semantic web technologies. To demonstrate its usefulness, we present a proof-of-concept illustrating how such a formalisation can be used to highlight potentially problematic derivations of sensitive features within a dataset.

Methodology

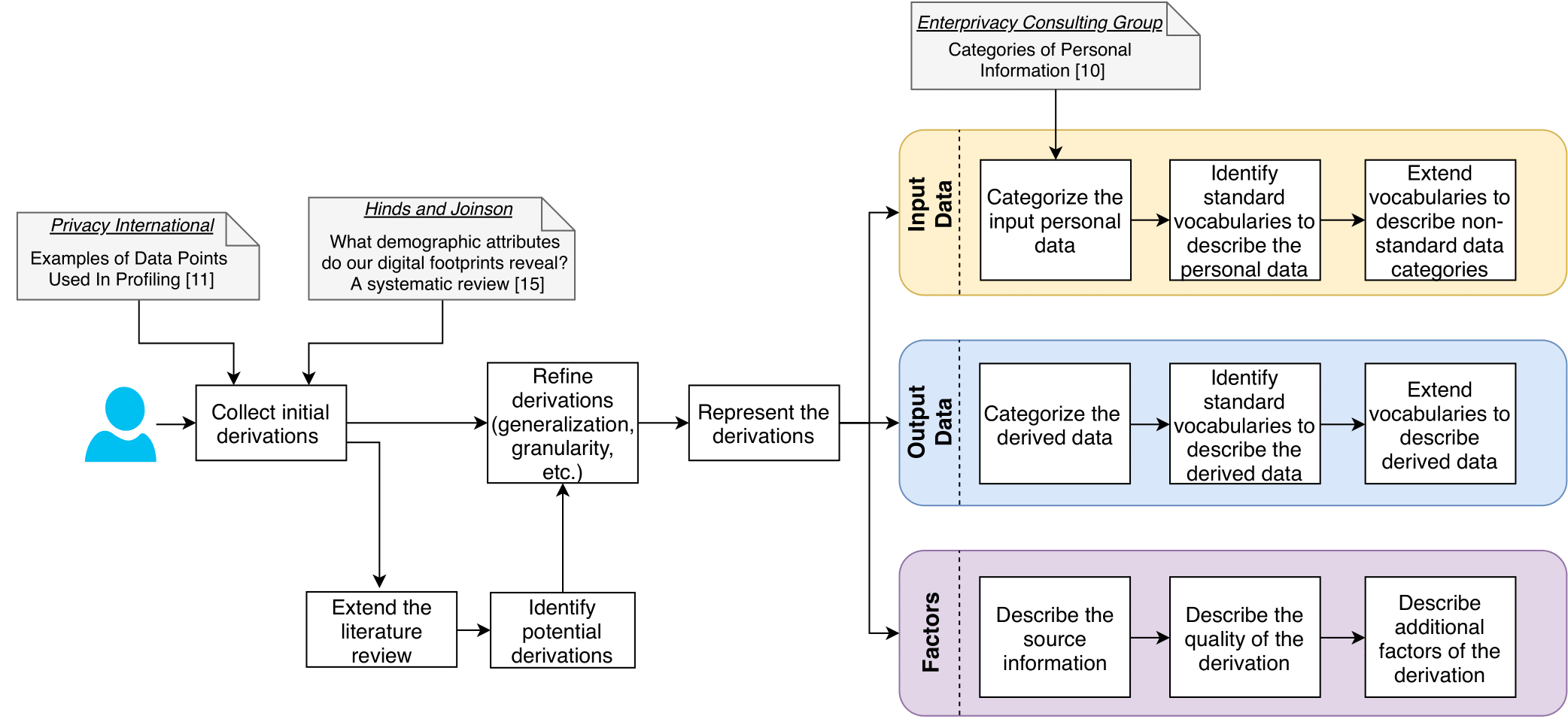

Figure 1 illustrates our methodology to arrive at a machine-readable catalog of personal data derivations based on a systematic and extended literature survey comprising of four main steps. We first collect initial derivations from two primary input sources: (i) a report by Privacy International [3] that describes documented derivations with references to source literature, and (ii) a recent survey [4] that reviews 327 studies that infer demographic attributes (mainly gender, age, location and political orientation) from “digital traces” (mainly social media, blogs and websites).

Starting from the two initial reports, we extend our literature review to cover a wider spectrum of derivations. Initially, we performed a keyword-based literature review based primarily on the topics of personalisation and user modelling. We then identified relevant derivations to select 13 additional papers1. In the future, we plan to open our catalog as a collaborative resource for the community. Then, we refine selected derivations. First, the collected derivations are represented using generation rules of the form {input → output[source]}, where source is a reference to the paper, study, tool, or report documenting the derivation. We found that most collected derivations contain ambiguous or coarse descriptions that do not necessarily detail automatic, machine-processable inferences. We clean and refine this data to prepare the derivation for semantic representation in the next step. Finally, we represent derivations in RDF and OWL to allow automatic, machine-processable inferences and querying of our corpus. A proof of concept prototype of the model is presented in Section 3. Methodologically, we (i) categorize input and output data, (ii) identify standard vocabularies to represent them, or extend/create vocabularies to cover novel needs, and (iii) represent additional meta-data for factors that influence or determine the derivation such as quality of derivation (e.g. methods that produce derivations with some percentage of confidence), and input requirements (e.g. minimum input data rate or frequency needed to perform the derivation). We focus on (i), whereas (ii) and (iii) are part of future work.

Proof-of-concept Implementation

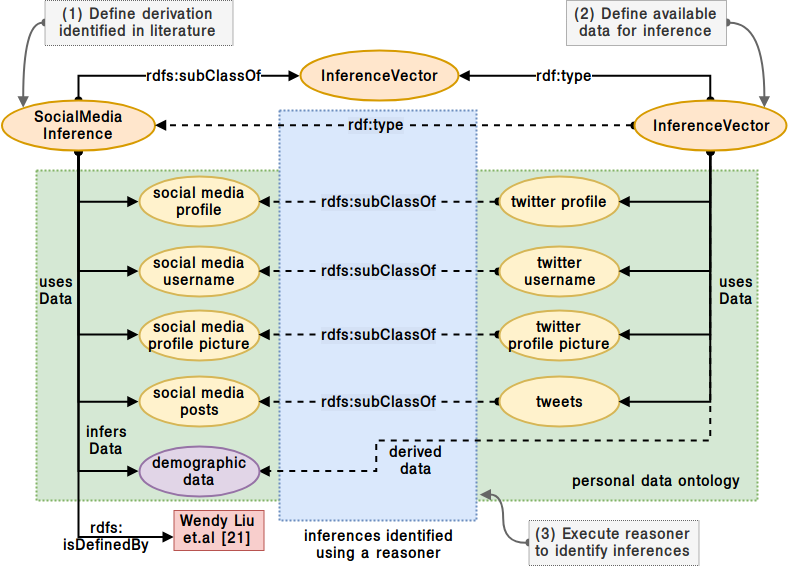

We present a proof-of-concept implementation[repo] that takes given data categories and identifies potential data derivations based in literature. We define personal data categories and their characteristics as an ontology using OWL2, starting with the taxonomy by Enterprivacy Consulting Group2, and then adding additional data categories from literature. We also define ‘dimensions’ such as source, medium, and format which are relevant to the method that derives data. Each inference is linked to the literature identifying its source for transparency.

In our ontology, data derivations identified from literature are defined as logical inferences using the class InferenceVector. The input data categories to the inference are specified using usesData, and the additional data categories produced as output are specified using infersData, with the source literature specified using rdfs:isDefinedBy. To define a derivation based in literature, we create a sub-class of InferenceVector using rdfs:subClassOf and associate it with data categories and relevant dimensions using these properties. To identify potential data derivations for a given set of personal data categories, we first represent derivations found in literature using InferenceVector. We then define a new instance of InferenceVector using rdf:type and associate it with given data categories using usesData. We then use a semantic reasoner such as HermiT3 to identify potential inferences for given data categories. The reasoner identifies defined derivations by matching their inputs (usesData) with given data categories (or their parent categories), and associates them with the instance using rdf:type relation. We then use a SPARQL query to retrieve the applicable derivations. A simplified example (single source, no dimensions) representing the derivation of demographic data from twitter [5] is visualised in Figure 2.

Conclusion and Future Work

This paper addresses the issue of transparency regarding how additional information can be derived from collected personal data. Our proposed approach assists in identification of potential data derivations using rule-based formalisation using semantic web technologies of derivations in literature . We presented feasibility of this approach using a proof-of-concept that uses an OWL2 ontology for representing personal data characteristics and derivations, and a semantic reasoner to identify potential derivations for given data categories. Our approach is useful in the identification of risks of such potential data derivations, and is aimed as a starting point for an open catalogue that documents known derivations of personal data towards raising awareness. As for future work, the foremost challenge lies in representing personal data information to sufficiently express its complexity, where we expect to use rule-based approaches such as SWRL. Also, to incorporate literature from Section 2, adding attributes such as identifiers, and recording use of techniques such as machine learning. The aim is to create an open community resource for documenting derivations for transparency.

Acknowledgements: This work is supported by funding under EU’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme: grant 731601 (SPECIAL), the Austrian Research Promotion Agency’s (FFG) program “ICT of the Future”: grant 861213 (CitySPIN), and ADAPT Centre for Digital Excellence funded by SFI Research Centres Programme (Grant 13/RC/2106) and co-funded by European Regional Development Fund.

References

[2] D. Quercia, M. Kosinski, D. Stillwell, and J. Crowcroft, “Our twitter profiles, our selves: Predicting personality with twitter,” in Proc of passat and socialcom, 2011, pp. 180–185.

[4] J. Hinds and A. N. Joinson, “What demographic attributes do our digital footprints reveal? A systematic review,” PLOS ONE, vol. 13, no. 11, 2018.

[5] W. Liu, F. Al Zamal, and D. Ruths, “Using social media to infer gender composition of commuter populations,” in Proceedings of the when the city meets the citizen workshop at icwsm, 2012, p. 4.

Prior Publication Attempts

This paper was published after 2 attempts. Before being accepted at this venue, it was submitted to: Annual Privacy Forum 2019