Explaining Disclosure Decisions Over Personal Data

International Semantic Web Conference (ISWC)

✍ Ramisa Hamed* , Harshvardhan J. Pandit , Declan O'Sullivan , Owen Conlan

Description: Representing and explaining disclosure of personal data using semantic web

published version 🔓open-access archives: harshp.com , TARA , zenodo

Abstract. The use of automated decision making systems to disclose personal data provokes privacy concerns as it is difficult for individuals to understand how and why these decisions are made. This research proposes an approach for empowering individuals to understand such automated access to personal data by utilising semantic web technologies to explain complex disclosure decisions in a comprehensible manner. We demonstrate the feasibility of our approach through a prototype that uses text and visual mediums to explain disclosure decisions made in the health domain and its evaluation through a user study.

Introduction

While individuals understand the value of their personal data, they are largely concerned with its potential misuse by businesses and governments [1], and bemoan the lack of a trusted entity that affords them control or advice regarding protection of their data [2]. Legislation such as the EU's General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)1 aim to preserve privacy by making data processing more transparent and accountable. Recital 71 of the GDPR additionally states the “right to explanation” for automated-decisions with significant effects for individuals. Providing more information and control is beneficial to all stakeholders as individuals who perceive themselves to be in control over the release and access of their private information (even information that allows them to be personally identified) have greater willingness to disclose this information [3].

This research believes that technology can be used for social good by having automated decisions over the access and disclosure of personal data if provided with transparent explanations of the decisions made. To this end, we present a framework for empowering individuals to understand how and why a decision was made regarding access to their personal data. We present the feasibility of our approach through a prototype for a use-case in the health domain. The prototype utilises semantic web technologies to explain complex disclosure decisions of a reasoning process through textual and visual representations.

Framework & Prototype Implementation

The aim of our framework is to enable individuals to understand automated disclosure decisions over their data by explaining the facts and logic for how the system arrived at a particular decision. The framework is comprised of the following components: (1) Data Resources: includes personal data and a knowledge base, comprised of - domain ontologies, privacy rules defined by individuals or regulation and logs that record decision history. (2) Actors: includes data owners - individuals to whom the personal data relates, and data requesters - entities that request access to personal data. (3) Functional Components: these include automatic and semi-automatic decision making units, a logger to record all decisions, and a context-discovery unit for gathering contextual information about actors for use in the decisions. The decision maker unit utilises a semantic reasoner over the collected knowledge-base and disclosure history to decide the response for access requests. These decisions are intended to be automatic with the decision explainer capable of providing an explanation, but can be semi-automatic where the decision maker does not have sufficient information or when the data owner needs to (manually) change a decision - in which case the confirmer obtains confirmation to make the disclosure.

We implemented a prototype using semantic web technologies with a focus on explaining the inference of semi-automatic disclosure decisions over personal data. It uses RDF/OWL to define the data graph, with human-readable information using rdfs:label for each node. The data disclosure rules are defined using SWRL [4] with a human-readable description. Requests for data access are added as triples using the Apache Jena API2, and the Pellet reasoner [5] is used to match requests with privacy rules, where matched rules are retrieved using SPARQL3 and indicate granted access to data.

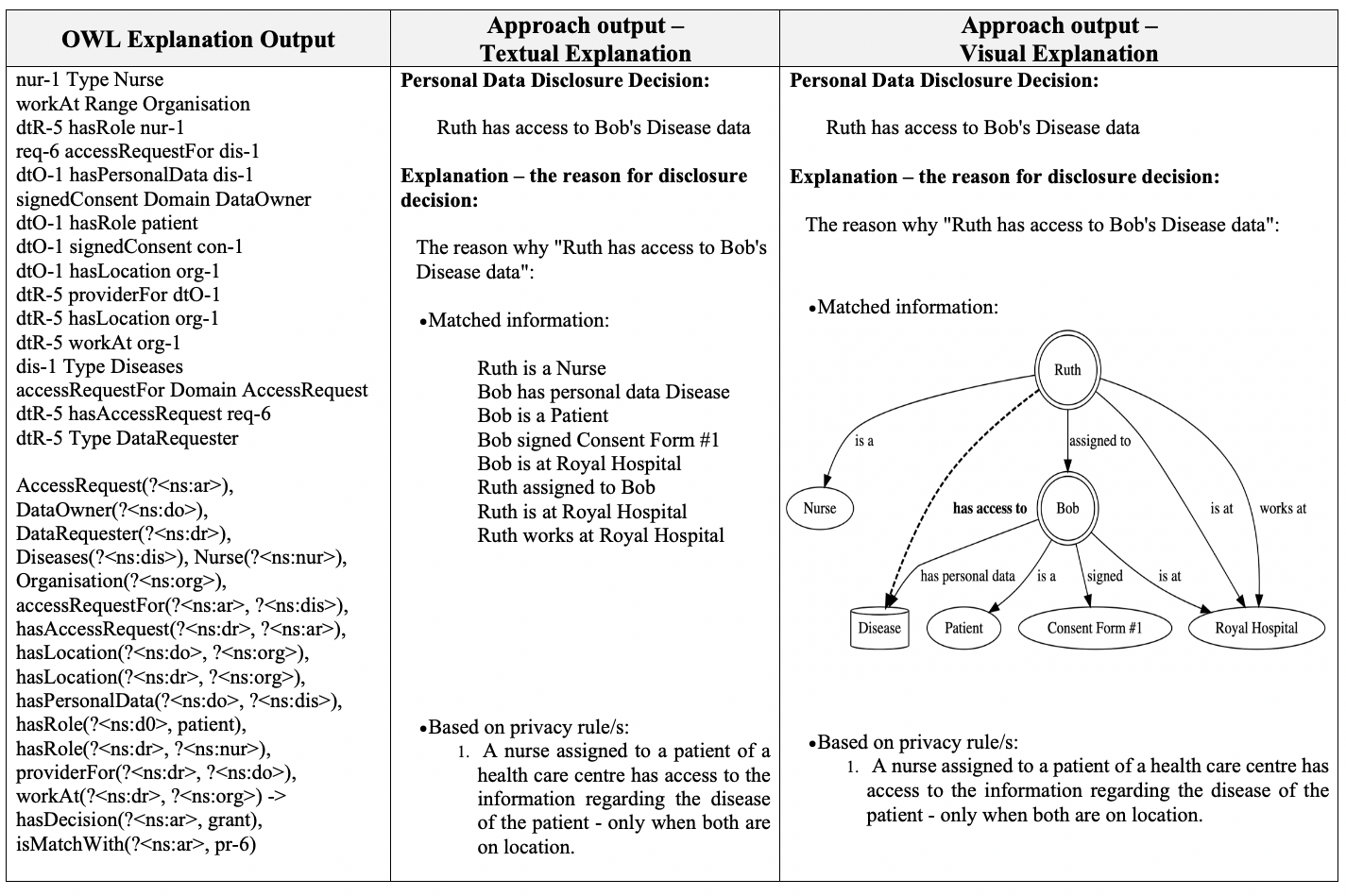

The explanation of disclosure decisions was provided using human-readable descriptions for entailments in the form of text and visual representation as depicted in Fig. 1. We used OWL Explanation [6] to obtain the entailment as a set of axioms consisting of the minimal subset of the data graph sufficient for the entailment and the corresponding SWRL rules used for making decisions. The axioms were filtered to remove ontological declarations, type information for instances, and domain/range information for properties. The access request was also removed as it is considered the outcome rather than an explanation. The axioms were then reduced by substituting type declarations with the rdfs:label of the declared concepts. Finally, text representations were generated by translating each triple into a statement, and visual representation were generated by using GraphViz4.

User-Study

The user-study consisted of participants being shown two scenarios with disclosure decisions and their explanation for issues in the health-domain [7]. Each user was shown a disclosure decision and its explanation with textual representation for one scenario and a visual representation for the other which allowed us to compare the understandability of textual and visual mediums for explanations. The users first had to provide explicit informed consent for the study, after which a questionnaire solicited users’ perceptions about disclosure decisions and access to data. The users were then shown two scenarios with their disclosure decision explained using a random permutation of textual and visual mediums. Each scenario was followed by a SUS5 questionnaire assessing usability, three comprehension questions and plus one attention question, followed by an ASQ questionnaire assessing satisfiability.

The comprehension questions enquired the user’s understanding of the explanation for disclosure decision. Two questions were multiple choice (MCQ), while one question was multiple choice with multiple answers (MA). The first question tested understanding of facts presented in the explanation, while the third question tested the understanding of another similar decision in the scenario. Scoring was as follows: correct choice for MCQ were awarded 1 point, while each option in MA was interpreted as a true/false choice, and awarded 1/n points with n representing the total number of options.

We used Prolific6 to run the user-study which consisted of paying users £2.50 for 25mins of their time. We had 21 participants with one user rejected as they failed to answer the attention question, giving us 20 participants who successfully completed the study. Results for SUS showed 73.88% for textual and 73.5% for visual indicating similar good usability for both mediums. Regarding comprehension, 75% users selected two or more (of three) correct answers for textual medium with 60% users for visual, while 15% of users got all the answers correct for textual, and 20% for visual. 70% of users correctly answered the first question about reason of access for both mediums, whereas 55% of users correctly answered the third question for textual and 65% for visual. For MA, all users selected at least one of two true answers where users on average scored 75.75% for textual and 70% for visual mediums, indicating similar levels of comprehension. This shows that while the explanations are comprehensible, they are currently not sufficient to enable complete understanding of the reasoning process. Similarly, users scored 77.15% for textual and 83.10% for visual mediums in the ASQ, indicating similar levels of satisfaction regarding explanations.

Conclusion and Future Work

This paper addressed privacy concerns regarding automated disclosure decisions over personal data using a framework that provides explanations to empower users to understand the reason of access to their personal data. The paper showed feasibility of the framework through a prototype implemented using semantic web technologies to explain disclosure decisions using textual and visual mediums. A user-study evaluation of the prototype showed the comprehension of explanations for both textual and visual mediums.

For future work, we plan to undertake user-studies involving more participants and complex scenarios. We also plan to incorporate graph-summarisation techniques and queries to improve our explanations.

Acknowledgement. This research is supported by the ADAPT Centre for Digital Content Technology, is funded under the SFI Research Centres Programme (Grant 13/RC/2106) and is co-funded under the European Regional Development Fund.

References

- T. Morey, T. Forbath, and A. Schoop, “Customer Data : Designing for Transparency and Trust,” Harvard Business Review 93.5 (2015)

- Web Foundation, “PERSONAL DATA: An overview of low and middle-income countries,” (2017).

- L. Brandimarte, A. Acquisti, and G. Loewenstein, “Misplaced Confidences: Privacy and the Control Paradox,” Social Psychological and Personality Science 4.3 (2013).

- I. Horrocks et al., “SWRL : A Semantic Web Rule Language Combining OWL and RuleML,” W3C Member submission 21.79 (2004).

- E. Sirin, B. Parsia, B. C. Grau, A. Kalyanpur, and Y. Katz,“Pellet: A practical OWL-DL reasoner”Web Semantics: science, services & agents on the World Wide Web 5.2 (2007)

- M. Horridge, B. Parsia, and U. Sattler, “The OWL Explanation Workbench : A toolkit for working with justifications for entailments in OWL ontologies,” vol. 1, (2009).

- B. Yüksel, A. Küpçü, and Ö. Özkasap, “Research issues for privacy and security of electronic health services,” Future Generation Computer Systems 68 (2017).

Regulation (EU) 2016/679. Official Journal of the European Union. L119, 1–88 (2016)↩︎

http://jena.apache.org/documentation/ontology/↩︎

SUS Questionnaire https://www.usability.gov/how-to-and-tools/methods/system-usability-scale.html↩︎

Prolific Academic https://prolific.ac/↩︎