Role of Identity, Identification, and Receipts for Consent

Open Identity Summit 2021 (OpenIdentity)

✍ Harshvardhan J. Pandit* , Vitor Jesus , Shankar Ammai , Mark Lizar , Salvatore D'Agostino

Description: Discussing how identity and identification for consent lead to receipts as an elegant solution; and introduces the PaE:CG project

published version 🔓open-access archives: harshp.com , TARA , zenodo

📦resources: Role of Identity, Identification, and Receipts for Consent

Abstract

This article outlines issues in the current ecosystem of data sharing based on consent and the role of identity and identification. It argues how the consent mechanism is hostile to individuals in the form of: (a) inscrutable third parties who remain largely unknown; (b) denying ability to identify and manage consent; and (c) lack of technological solution. The article discusses the role and feasibility of Consent Receipts, and presents its role in the Privacy as Expected: Consent Gateway (PaE:CG) project for the future of accountable identity and identification mechanisms for consent.

Introduction

Consent in the context of data protection and privacy laws is a legal basis that affords individuals control and choice over the processing of their personal data. Though laws such as the GDPR do not explicitly mention requirements regarding identity or identification of Data Subjects, it is implied for Data Controllers to establish that the Data Subject or an authorised agent on their behalf is exercising consent or rights. Where individuals already interact with services using identifiers, such as through accounts, the exercising of consent and rights does not need a separate identity and identification process. However, there is no mutual agreement on identity where individuals only interact with the service in the context of consent, such as through a cookie/consent dialogues. As a result, when the individual wishes to exercise their rights in connection with the choices made regarding consent, they have no way to indicate their identity and the service in return has no form of identification with which to validate the individual’s right to access and change their consent.

Controllers, or more specifically their websites, get around this problem by using ephemeral or transient solutions such as ’cookies’ to store the information associated with given consent, and use it to enable the individual to later revisit the website and change their choices, usually through dedicated consent management interfaces. Apart from the fact that such interfaces and processes are under question regarding their legality [1], their use is problematic given that: (a) exercising rights is conditional on existence of the cookie; (b) it is non-transferable to other devices or browsers; (c) the individual has no mechanism to demonstrate or challenge their consent; and (d) no coherent way individuals to manage consent through cookies given obfuscation and lack of tools/mechanisms.

On the other side of this perspective, individuals often do not understand the existence and scope of entities they often share consent with, which is is compounded by the issue termed the “biggest lie on the internet”[2] that individuals are not aware of or do not comprehend the ‘policies’ and ‘notices’ shown online, yet agree to the presented conditions. Existing research has shown the malpractices of consent in terms of ‘dark patterns’ that manipulate and coerce consent [1] the large-scale anonymity and inscrutability of third-party recipients of data [3]. The California Consumer Protection Act (CCPA), passed recently in 2018, provides a mechanism for ‘opting-out’ of what it terms as ‘selling’ data to such third parties, and mandates the provision of a ‘do-not-sell’ option on websites. However, the issue remains that there is no method to identify which recipients the data has been ‘sold’ to, and to track their acceptance and enforcement of ‘do-not-sell’ right.

Consent Receipts

The Consent Receipt specification [4] was created by the Kantara Initiative to define an interoperable record for facilitating management of consent for both the Data Subject and the Controller1 by representing metadata and context associated with given consent, and providing a unique ID for the receipt as a shared identifier for Controllers and Data Subjects to refer to consent - with the option for the receipt to be signed by the Controller.

The use of a Consent Receipt helps with the issue regarding identity and identification as it permits the Data Subject and Controller to use and refer to the same common shared record in their communication and exercising of rights. Where the Controller cryptographically signs the receipt, it also presents the possibility to use it as documentation for the Controller’s accountability by utilising the receipt as proof of consent transaction. The Consent Receipt in its current form (v1.1) has, amongst other, two significant gaps: (i) records do not concern authentication or verification of entities and information; and (ii) requires proactive participation by Controllers. Despite these shortcomings, the larger argument of using receipts as a proof and record of transactions, and its potential for establishing trust through transparency and accountability remains valid as outlined in ‘web of receipts’ [5].

Receipts, as an artefact, can aid in establishing the identity and proof of an interaction or a transaction regarding consent [5]. However, in order to perform these actions, the parties involved must agree on the methods and infrastructure used in identification and verification. There is also the issue of support and implementation by all parties involved in the receipt process - the Controller to create and issue the receipt, the web-browser or device as an agent of the Data Subject to receive and store the receipt, and the ability to inspect and verify receipts independent of either party. In its current form, the onus of receipt creation and provision is on the Controller - which diminishes its effectiveness for bad actors and prevents Data Subjects from proactively recording or challenging consent claims.

However, the concept of ’receipts’ as an accountable record is gaining interest and traction. The Advanced Notice and Consent WG2 (ANCR) at Kantara is currently working to update the Consent Receipt specification to address the recent legal requirements and privacy challenges. The recently published ISO/IEC 29184:20203 standard for Online Privacy Notices and Consent defines criteria and controls for consent collection and uses the Consent Receipt specification as an example of a machine-readable consent record. Additionally, the ISO/IEC 275604, currently in drafting stage, is intended to provide a standardised implementation for consent records.

Privacy as Expected: Consent Gateway (PaE:CG) Project

PaE:CG is funded under the EU H2020 Next Generation Internet’s (NGI) TRUST project funding programme which promotes development of innovative solutions for management of consent by utilising privacy enhancing technologies (PETs) such as cryptography and federated identity. The driving principle for PaE:CG is utilising receipts for an accountable mechanism while ensuring the Internet as it currently is and should remain for the most part a pseudo-anonymous space, while still empowering individuals with choice and control through consent. PaE:CG thus extends the existing paradigms of Consent Receipt, cryptographic identity and verification, and online identities to defining specifications and create implementations for information structures and processes across three levels: (i) service provider; (ii) end-user; and (iii) a notary or witness - a radical new concept introduced by the project to counter non-participation by some entities within the consent transaction. The project rationale and objectives can be explored in more detail via its website https://privacy-as-expected.org/.

Consent Receipts within PaE:CG

Within the PaE:CG vision, consent receipts work as expected - they are generated for a transaction and are shared (copies) between the Controller and the Data Subject. What PaE:CG does differently is provide the ability to any entity for generation of receipt, thus permitting any participant to produce a record without relying on the goodwill or accountability of others. The receipts are to be signed, which provides guarantees regarding who produced it, at what time, and the receipt itself is meant to record the context of consent. The PaE:CG version of receipts thus enables individuals to claim records where a controller does not provide any record or receipt, and conversely also enables controllers to produce records for their own transparency and accountability where individuals do not participate in the process. Ideally, both controllers and individuals would participate and sign the receipt to ensure the highest degree of accountability for all parties.

The PaE:CG specification defines protocols for use of bearer tokens to provide cryptographic guarantees regarding identity when receipts are generated and signed. This permits the receipt to be used for identification purposes for that specific interaction, and additional possibilities to be used further in exercising related rights such as modification or withdrawal of consent. For controllers and service provides, receipts thus provide a convenient way to build and maintain trust based on accountability, and also offer the possibility of creating self-service points that utilise receipts to manage consent and personal data without additional forms of identities. This also provides an avenue for building innovative solutions towards other new and novel forms of data sharing and controls which can be based on decentralised identifiers.

The verifiable identity protocols used in PaE:CG receipts provide a ‘proof’ and ‘record’ of consent along with pertinent information required for legal compliance and complaints. For this, the identity of Data Controllers and Third Parties need additional introspection owing to their role in the collection, use, and sharing of data. PaE:CG therefore looks towards utilising the existing identities of controllers expressed through their websites and domain names, and extends it with requirements to associate them with a legal identity. This has the additional benefit of utilising the existing mechanisms of secure identity and information based on internet and web protocols. For example, to express that consent was collected on a specific website by the specified legal identity, the information from the website’s public keys and certificates that the web-browser already verifies as part of secure connections could be potentially reused as a form of record and identity.

Witness to Notarise the Consent Record

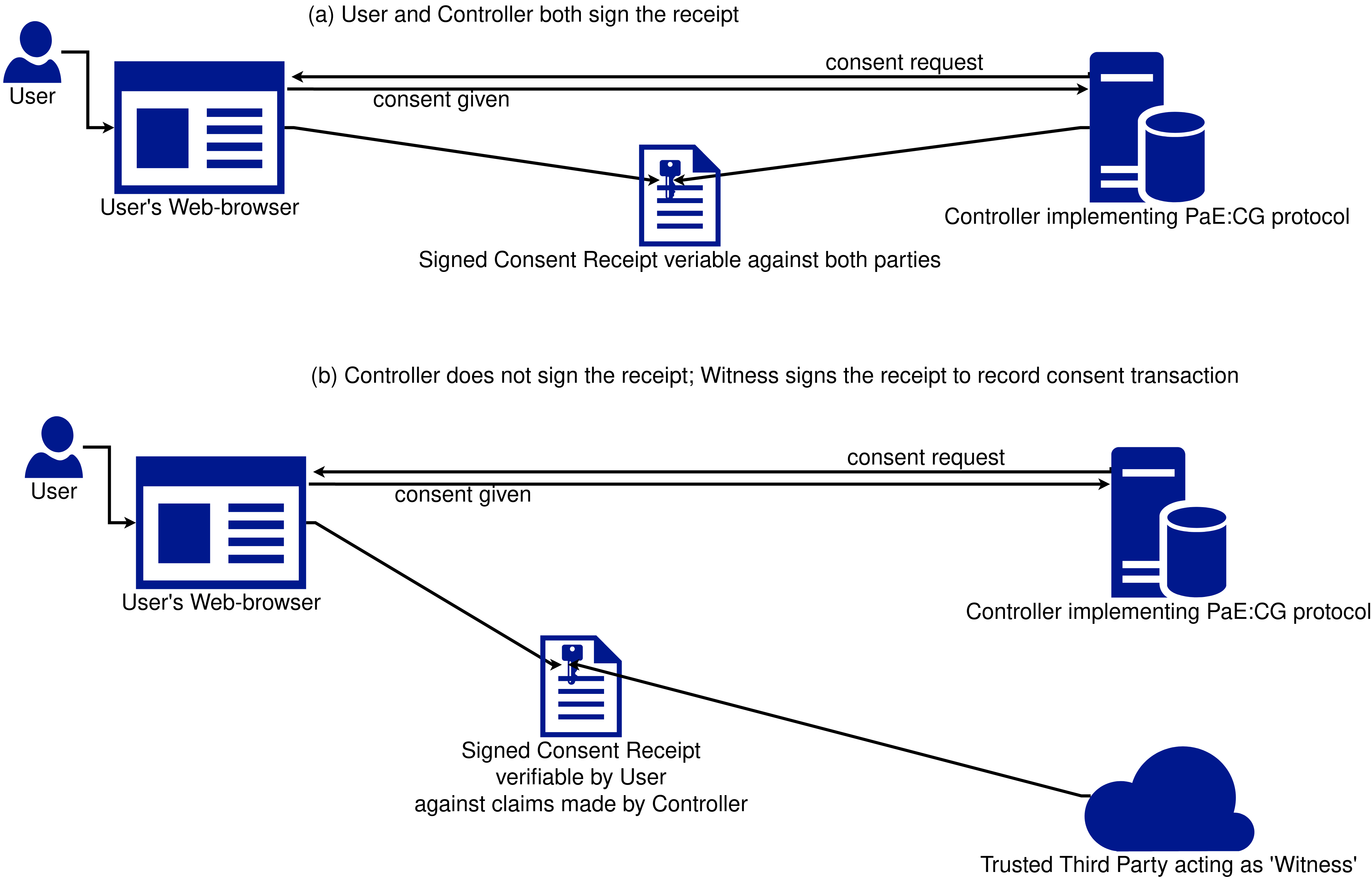

When Controllers support the use of receipts natively by implementing PaE:CG protocols, which is the ideal use-case, the interface and use of receipts is seamless for all parties. Ideally, each Third Party would also sign the receipt for complete transparency and verifiability. However, implementing such radical protocols would take time and require support, and it is expected to face barrier through non-conformance and resistance. With this in mind, the real innovation in the project concerns where Controllers or Third Parties do not support the PaE:CG protocols, and thereby do not provide receipts.

Rather than abandon the usefulness of receipts, PaE:CG allows a trusted third party to act as a ‘witness’ or ‘notary’ to the consent interaction by signing the receipt, as depicted in Fig.[fig:paecg]. Witnesses solve the problem of transparency and auditability of organisations on the web, and allow for any party - whether it be the Data Subject, or Controller, or Third Party, to produce verifiable records as a form of claim. For Data Subjects this provides a way to hold organisations accountable, whereas for Controllers this provides a way to document their involvement in transactions - such as scope of data sharing with a Third Party.

The difference between a Controller and a Witness is the accountability that goes along with signing of the receipt. When a controller signs the receipt, it indicates a binding claim of practices conducted by that entity. Whereas when a witness signs a receipt it indicates that the other party (or parties) have made the specified claim - which can be used as a form of documentation that can be verified to be produced at a specific time and context. As the witness is agnostic to the other entities, it can be used by either the Controller - for example to record that the individual has consented to specific purposes; or by the individual - for example to record that they consented to only some purposes. Extending the application to other avenues of accountability, the PaE:CG protocols and the use of a Witness permits individuals to also generate and demonstrate verifiable claims such as refusing consent to some party or recording information offered in a consent request.

Conclusion

PaE:CG thus updates the Consent Receipt specification for use with the recent legal developments while ensuring its practical accountability and implementation using protocols based in cryptography. This will enable and encourage a new category and level of transparency on the internet through use of receipts as an artefact that identifies parties and holds them accountable. The novel concept of a Witness is promising as it provides a way for both controllers and individuals to record claims made within specific contexts that can be later demonstrated and verified. In addition to practices of accountability, the utilisation of a receipt containing signatures provides a form of identification which can be used to conduct further interactions regarding consent - such as its modification and withdrawal. The identification also provides an accountable mechanism for claims of misuse or disputes regarding the interpretation of consent. Where one of more parties - such as the Controller or Third Parties - do not participate, the possibility to utilise a witness to sign instead provides a measure of trust and verification to the claim in such cases.

Apart from providing specifications and reference implementations, PaE:CG project also provides novel avenues for further work and research into utilising existing identity and accountability mechanisms for trust, verification, and consent - especially those utilising web protocols and standards. To encourage such research, the project is contributing its work to the ongoing development of Consent standards at both ISO/IEC and Kantara and has pledged to disseminate its deliverables under open and permissive licenses.

Funding Acknolwedgements: This work has been funded under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme NGI TRUST Grant#825618 for Project#3.40 Privacy-as-Expected: Consent Gateway. Harshvardhan J. Pandit is also funded by Irish Research Council Government of Ireland Postdoctoral Fellowship Grant#GOIPD/2020/790; and ADAPT SFI Centre for Digital Media Technology funded by Science Foundation Ireland through SFI Research Centres Programme and co-funded under European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) through Grant#13/RC/2106_P2.

References

- Use of ISO terms in Consent Receipt is replaced here with their GDPR equivalents for consistency↩︎

- https://kantarainitiative.org/confluence/pages/viewpage.action?pageId=140804260↩︎

- https://www.iso.org/standard/70331.html↩︎

- https://www.iso.org/standard/80392.html↩︎